How to Fix CMMI Models

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveHealthcare 101 Crash Course

%2520(1).gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

This episode of Out-Of-Pocket is brought to you by…

Stedi is the modern healthcare clearinghouse. We help you process eligibility checks, claims, and remits.

With Stedi, you get more than best-in-class APIs and infrastructure. You also get world-class support.

Every Stedi customer gets a dedicated Slack or Microsoft Teams channel. Our average response time is less than 10 minutes. And you can try us for free.

—

Did that banner ad feel so natural and blow you away? Why don’t we chat on how we can do that for your company?

That which we call a CMMI Model

For anyone that talks about value-based care, the epicenter is really the CMS Innovation Center or Center for Medicare and Medicare Innovation (CMMI). It inexplicably has two names, for some reason has two Ms for Medicare and Medicaid when CMS doesn’t, and a bunch of other name related nonsense I don’t want to go into.

If you love or hate value-based care, this is who you should be congratulating or shaking an angry fist at.

CMMI has been coming out with a bunch of new models in the last year. But everyone has a different opinion on what they think the POINT of these new models should be. Is it to save money? Is it to test what works so others can replicate it? Is it to force hospitals to bend the knee?

So I thought it would be good to team up with someone who was actually involved with CMMI. Today is a guest post from Ankit Patel, who was a senior advisor for CMMI, and has some opinions about it. I like to bring some specific opinions and viewpoints into this newsletter every so often, I thought this would be a fun discussion 🙂.

Writing is Ankit’s, memes are Nikhil’s, opinions are rated E for everyone.

ACA Mandate

The Affordable Care Act created the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI)

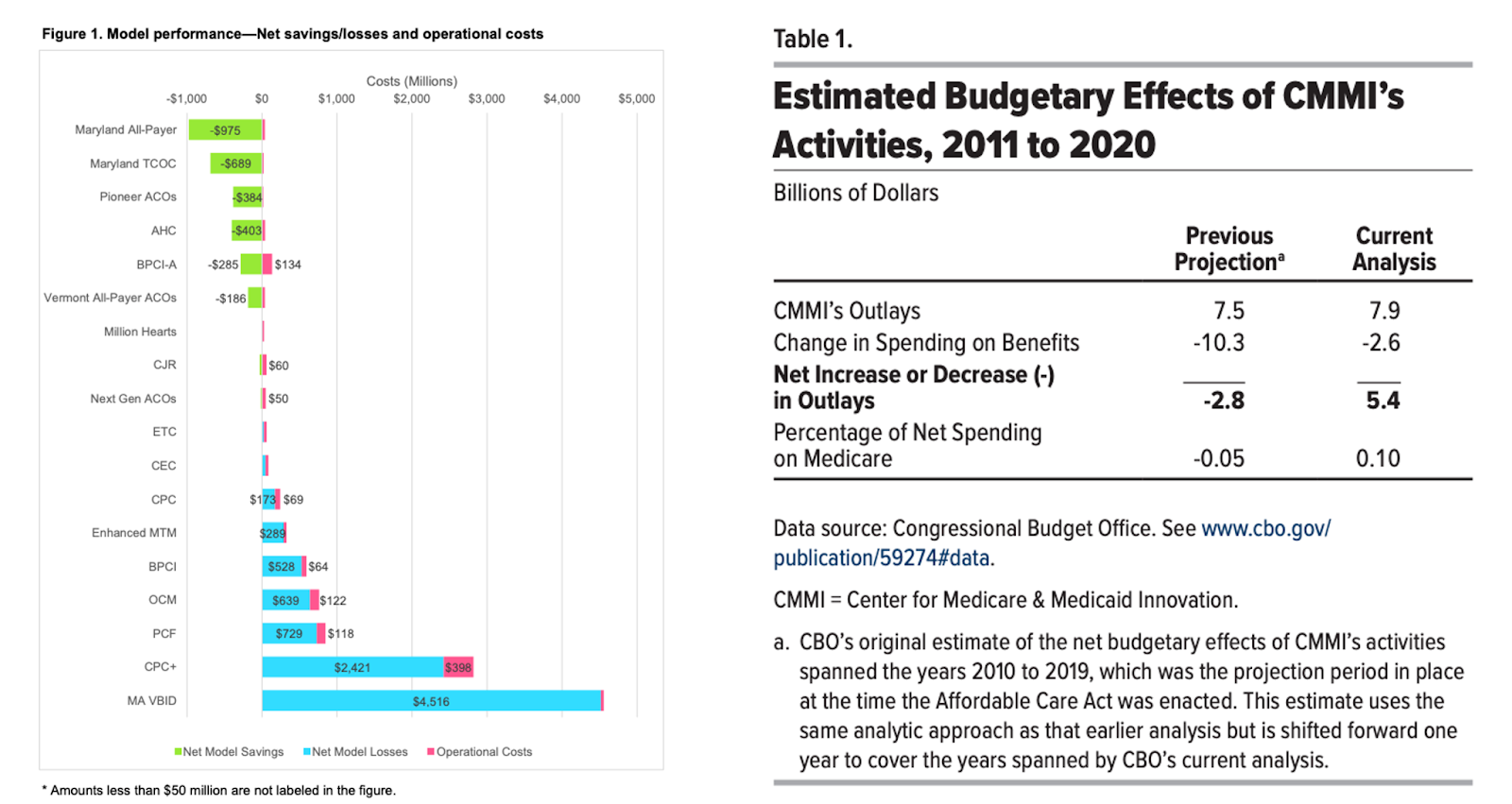

to test innovative payment and service delivery models to reduce program expenditures and enhance the quality of care furnished under the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Fifteen years in, only a handful of initiatives have saved money and the overall effort has been a net loss for American taxpayers. Last year, the agency announced a rebalancing of its portfolio. While it has made changes, the agency should consider a much broader shift in its strategy and approach.

CMMI is required to report its findings based on the tests that it conducts. Unfortunately, across various evaluations and reports to Congress the agency has been unable to articulate

- what interventions took place

- which actually worked

- And most importantly why they worked or didn’t.

The lack of research driven insights is not an accident. Rather than designing models to validate hypotheses, CMMI has sought to operationalize a preconceived vision of cost control - constraining excessive utilization, specifically hospital utilization. Under this vision, reduced utilization became a targeted outcome rather than a variable to be tested.

CMMI’s core mistake is trying to address hospital-spending by changing how physicians get paid. In Medicare’s original design: Part A is the insurance benefit for expensive hospital stays, while Part B was built to ensure seniors can access physicians. It's a curious design to push system-level cost control onto Part B, because you’re holding doctors accountable for costs driven by hospital prices and facility billing rules they can’t fully control. This is effectively asking doctors to function as insurance-style risk managers.

Quick interlude from Nikhil: Slack applications closing soon + Healthcare 101

OOP slack applications are due 2/27. I put this application out once a year. In particular we’re looking for more perspectives from:

-Dentists

-Optometrists

- People that work in hospital admin

-People that work at compounding pharmacies

-Pharma/Biotech

-CDMOs and CROs

-Brokers and Benefits consultants

-HR/CFO at self-funded employers that makes benefit decisions

-Lawyers smart about healthcare

-Doctors/Surgeons/MAs/LCSWs/nurses/NPs and all other frontline staff

- Anyone that works at a PBM, we have lots of questions

- Anyone that works at traditional RCM vendors or clearinghouses

- Anyone that works at a large health insurer

- Anyone that works at a stop loss insurance, MGU, etc.

More details and application is here. If you use AI, I will know trust me.

And also, if you don’t understand any of this value-based care mambo jumbo that Ankit is talking about, we will teach you in our upcoming healthcare 101 course taught by yours truly! We go through everything from the different payers, how hospitals spend money, what’s the deal with EHRs, and even an entire section on value-based care and how it works.

It’s virtual, 3/23 - 4/3. Email me for group discounts or sign up here yourself.

Back to our current programming with Ankit.

Current Testing Limitations

True testing involves manipulating individual variables within the healthcare system and measuring the resulting observations to validate or refute policy assumptions. But a few things have made it difficult to figure out what we should be learning from these experiments.

Multiple Variables

First, CMMI programs attempt to manipulate multiple variables at the same time which is making it nearly impossible to isolate the true cause of an observed outcome. Testing interventions in healthcare is like making pancakes from scratch: when you change the flour, the milk, and the sweetener all at once, you may know the final product is better or worse, but you won’t know why.

Likewise, CMMI evaluations describe observed outcomes but rarely identify specific interventions that drove them. More troublesome for an agency seeking to inform national payment policy is an inability to define the conditions under which those outcomes can be replicated.

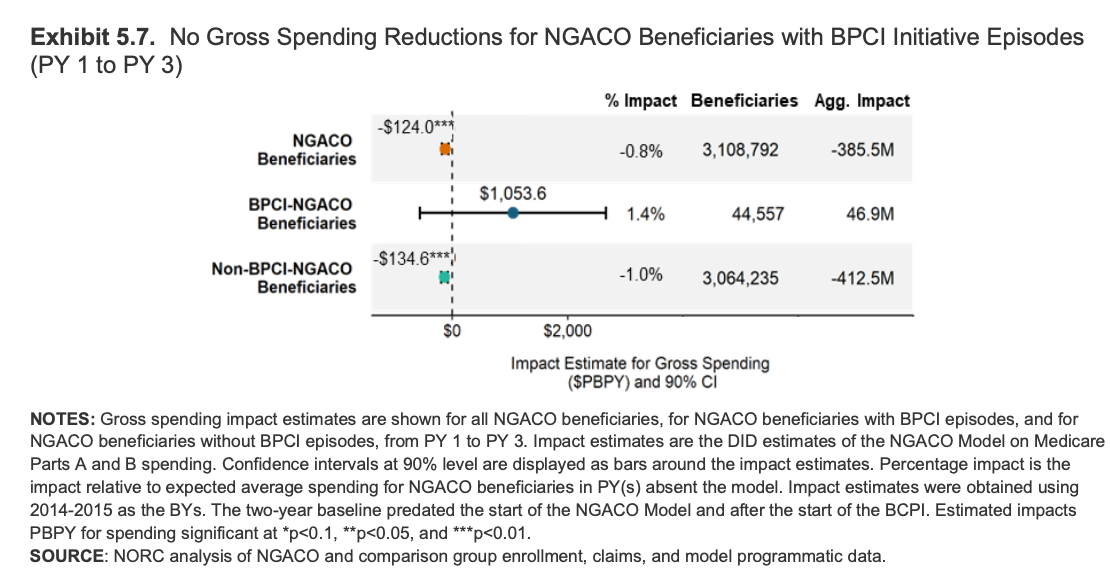

The Next Generation ACO (NGACO) program evaluation released in early 2024 highlights this issue. NGACO was comparable to the existing Shared Savings Program (SSP) but with several distinct features.

- How patients were assigned: Next Gen “pre-assigned” patients to the ACO up front (prospective attribution). The regular program mostly assigns them after the fact based on where they actually got care (retrospective attribution).

- What counted in the savings math: Next Gen included certain big hospital-related payment adjustments (IME and DSH) when calculating savings, while the regular program left those out.

- Extra incentive money: Next Gen gave participating groups additional funding to push things like Annual Wellness Visits. Regular ACOs did not receive this.

And yet, policymakers and taxpayers are left with little knowledge gained on the impact of these features. Which attribution methodology should be applied in what contexts? Should hospital payment adjustments be included or excluded in payment models? The most direct analysis offered in CMMI’s evaluation is that paying for more annual wellness visits results in more annual wellness visits. Water is wet, Nikhil dresses weird, we don’t need to analyze obvious truths. Surprisingly there was no analysis on if and when AWVs add meaningful clinical value for patients!

By the way, we didn’t even talk about the fact that participating organizations can be in multiple value-based care programs at once. So you have to do subgroup analyses to figure out if THAT caused differences itself, which includes all the tested variables in those programs.

In contrast to the multivariable approach, CMS has concurrently implemented major payment changes with little testing at all. For example, in 2018, CMS launched Remote Physiologic Monitoring (RPM) codes, offering reimbursement for digital health monitoring services. These codes were implemented without any prior testing by CMMI to evaluate provider behavior, oversight mechanisms, or clinical effectiveness. By 2024, the Office of Inspector General found that up to 43% of Medicare beneficiaries may not have received RPM services as intended and that CMS lacks key information needed to oversee the program. A well-designed CMMI RPM pilot could have revealed implementation challenges and surfaced fraud, waste and abuse risks before a broader rollout.

Counterfactuals

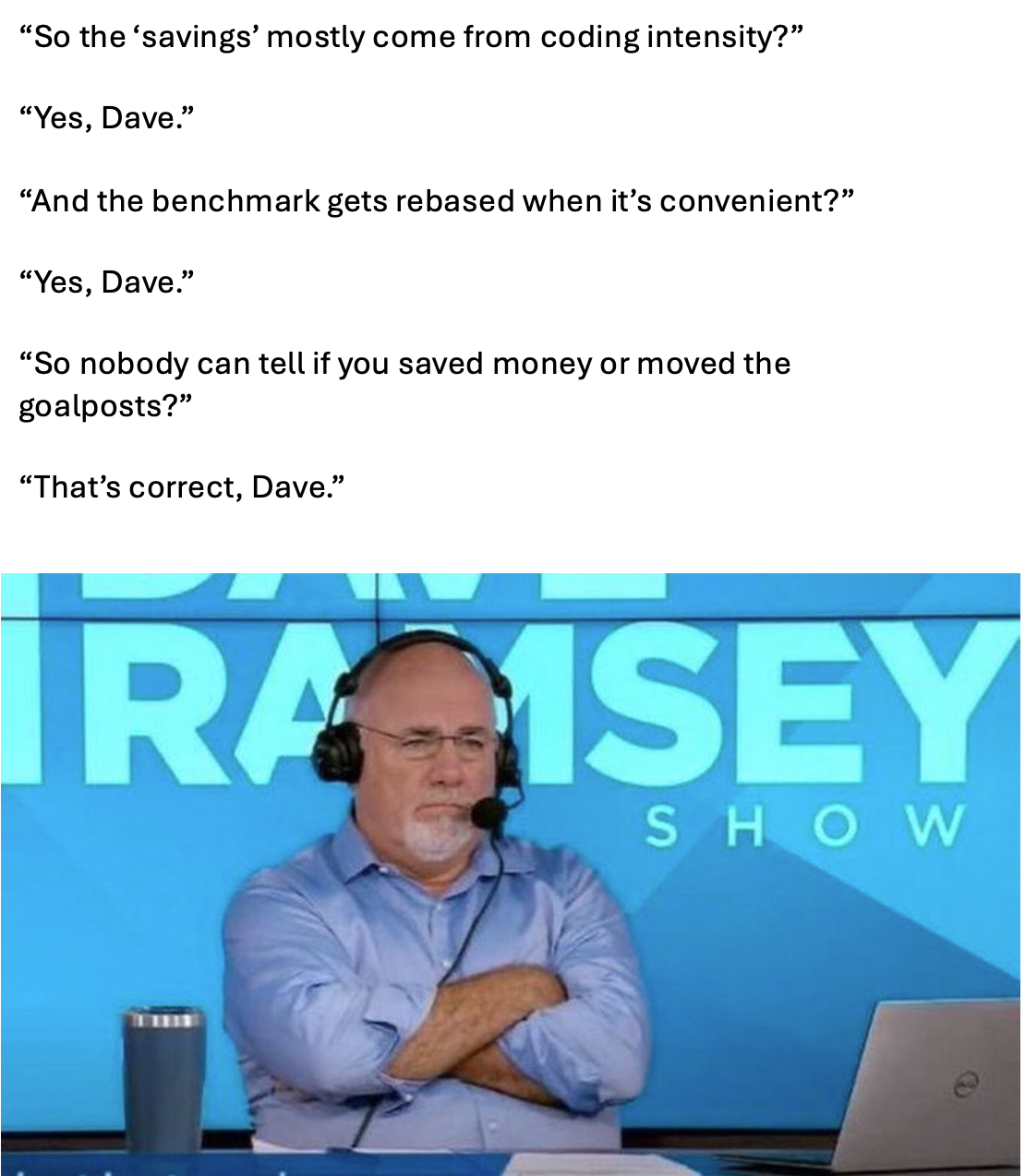

CMMI’s approach to producing desired outcomes is by creating counterfactual spending targets and placing physicians at financial risk for achieving them. But constructing counterfactuals is necessarily a difficult exercise that produces complicated methodologies requiring specialized knowledge to understand. A healthcare system already stretched thin has little capacity to interpret byzantine incentives and targets.

CMMI’s flagship program, ACO Reach, is a prime example. To establish a counterfactual spending target for physicians, one of many methodological components compared the reference population under ACO Reach with the reference population under the Medicare Advantage program. If spending patterns deviated by more than 1% a complex adjustment is triggered - the Retrospective Trend Adjustment (RTA). The RTA was partially applied however: 100% for deviations up to 4%, 50% between 4% and 8%, and none beyond that.

It is highly implausible that practicing clinicians focused on patient care could even understand this methodology, let alone modify their care accordingly. Do you even understand what I just wrote? Evaluators are then left to measure whether a likely misunderstood or unnoticed incentive happened to yield a favorable outcome.

Intermediaries

For many past CMMI models, participation occurred through corporate entities and their single Tax Identification Number (TIN). Notably, you didn’t have to be a hospital or provider to participate - you could be a newsletter writer in Gowanus. [NK note: hey] The complexity of programs with multiple moving variables and counterfactual targets has led CMMI to offload the administration of these programs to third-party intermediaries.

Many of these entities profit from navigating convoluted financial structures but do not test new clinical models. Some even just pick the model that pays them the most with their existing operations. By centralizing risk within intermediary entities, individual practices may be shielded from making more difficult operational or clinical changes. Financial aggregation can substitute for genuine care transformation.

CMMI's model designs have also structurally excluded the types of organizations most likely to innovate at the point of care. Minimum beneficiary thresholds (one of the lowest is 5,000 for new entrants in ACO REACH) automatically disqualify most independent and small group practices from direct participation.

Last, as insurance operators, intermediaries follow a cardinal rule of risk management: the larger the pool of patients under management, the easier it is to diversify financial risk. Growth and consolidation become rational priorities, often taking precedence over experimentation with new care delivery approaches. This strategy is resource-intensive and typically requires significant external capital, introducing additional expectations to manage for operating decisions.

These competing organizational priorities - managing program selection, scaling to stabilize risk pools, and raising capital to fund operations - are not inherently problematic. However, they complicate the evaluation of model performance. Observed outcomes may reflect organizational strategy as much as changes in care delivery. As a result, evaluations are often limited to determining whether the combined effects of these layered objectives produced a favorable result. Predictably, sometimes they do and sometimes they do not, but for reasons that remain unknown.

Plus, when participation is funneled through a narrow set of large intermediaries, the agency loses the variation it needs to learn. A five-physician primary care group in a mid-size city will approach care redesign differently than a PE-backed enablement platform managing risk across 30 states. More types of participants means more natural variation, which means more opportunities to isolate what actually works. A little competition never hurt.

A Path Forward - Will The New Models Change This?

Over the past year, CMMI has made meaningful efforts to address past shortcomings. It has sought to reduce the complexity of shared savings benchmarks and build clearer pathways for incentives to reach frontline providers rather than remaining concentrated at the level of convening entities. These steps reflect an awareness that prior models were overly complicated and administratively burdensome.

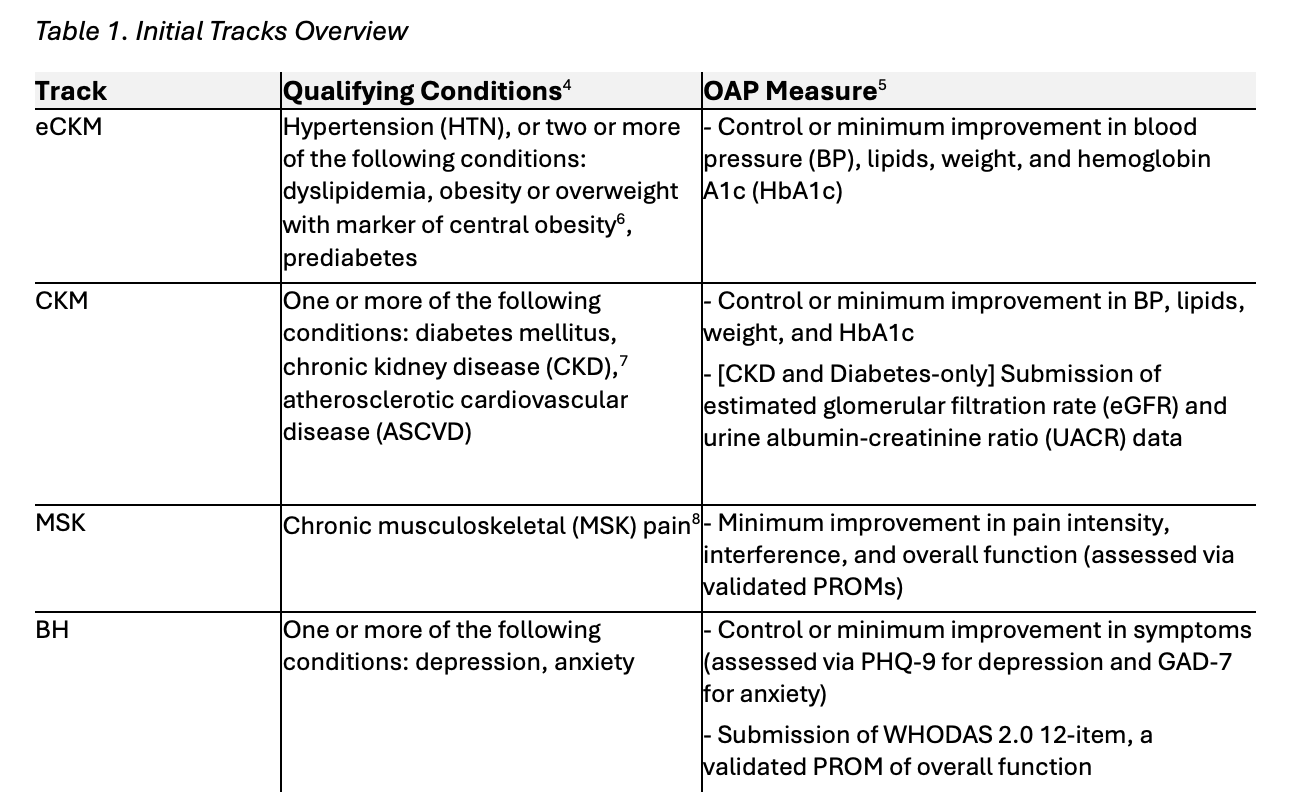

The agency is also beginning to test more discrete interventions. New initiatives such as MAHA ELEVATE are designed to directly measure the impact of functional and lifestyle interventions, while WiSER tests a structured pre-payment review process of selected services. The recently announced ACCESS model refreshingly focuses on testing improvements in specific clinical measures such as blood pressure rather than total cost of care and does so through active Medicare Part B–enrolled providers rather than through intermediaries.

These models represent a welcome shift toward more targeted experimentation. However, they do not yet represent a structural departure from CMMI’s core design paradigm. Operational refinement is not the same as methodological change. For example, the ACCESS model seeks to “reward outcomes rather than defined activities.” While appealing in theory, an outcome-focused approach that does not isolate the pathways to those outcomes risks bundling multiple behavioral and financial interventions together against counterfactual targets. Even if outcomes improve, it will still be difficult to determine which specific clinical or organizational changes drove the result.

Similarly, the agency continues to support large-scale total cost of care models such as LEAD, a successor to ACO REACH, that rely heavily on intermediary entities and complex counterfactual benchmark methodologies. These structures prioritize broad financial accountability over isolating discrete clinical interventions.

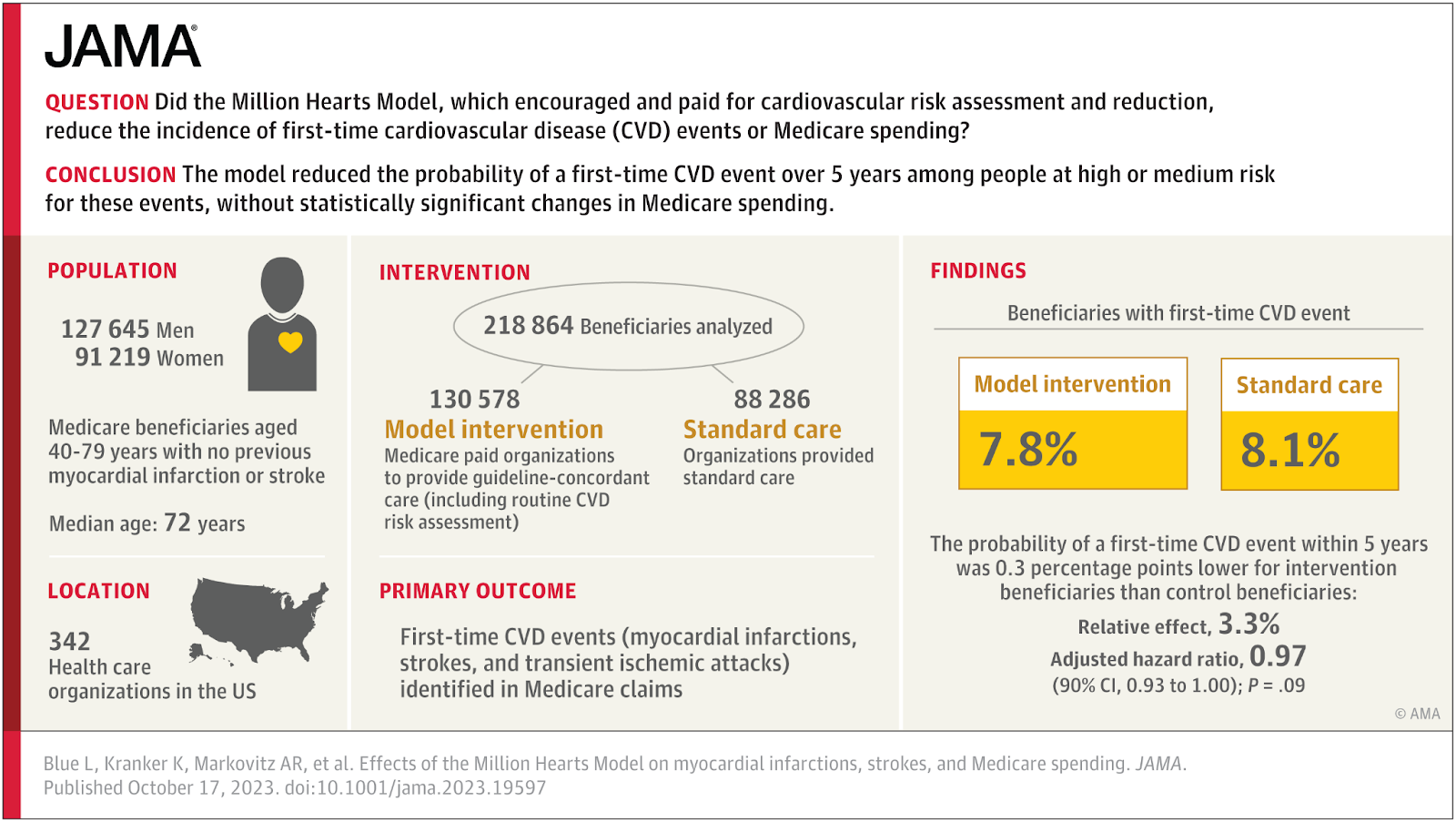

As an alternative, CMMI should build successors to focused demonstrations such as the Million Hearts Campaign, a federal initiative that targeted specific, evidence-based cardiovascular interventions, which showed that testing clearly defined interventions can generate meaningful policy insight.

To build on its recent positive steps, CMMI should consider additional operating principles to help it recommit itself to its Congressional mandate and contribute more meaningfully to the health policy discussion over the remainder of its funding cycle.

- Test Fee-For-Service Activity: CMMI has an opportunity to test and reform the FFS system. For example, if the agency is seeking to test the value of Annual Wellness Visits, a simpler approach directly incentivizing AWVs may suffice. A straightforward test could pay $1,000 for an AWV and then observe clinician behavior changes and patient outcomes.

- Separate Part A and Part B: As described above, the Part A and Part B programs were built on different foundations with different operating frameworks. Payment innovations that test Part A providers’ ability to improve the Part A program and Part B providers ability to improve the Part B program are likely to yield clearer insights than attempting to influence hospital outcomes using physicians as levers or vice versa.

- Engage Hospitals: CMMI has been reluctant to test a standalone federal hospital global budget model within traditional Medicare despite the success of the Maryland All-Payer Model. Rather than building on that experience with a direct Medicare hospital global budget demonstration, the agency has largely left global budget experimentation to state-led initiatives under the AHEAD model where it is paired with statewide total cost of care requirements. A direct Medicare hospital global budget model, tested independently of physician cost-containment mechanisms, would allow policymakers to isolate the hospital payment variable and assess whether hospital-level budgeting alone can replicate prior successes and improve efficiency and patient outcomes.

- Avoid Intermediaries: CMMI should continue to test at the actual level of clinical practice as they are proposing to do with the ACCESS Model. Providers already register their Tax ID (TIN) and National Provider Numbers (NPI) with Medicare for purposes of billing and reimbursement. Directing payments to TIN/NPIs that have been directly billing Medicare, say for three years, would allow testing at the point of care with established care providers.

- Limit Size: Despite its testing challenges, CMMI has continued to expand its portfolio. By 2024, more than 53 million individuals were affected by the agency’s programs - more than double the number just four years prior. Models should be limited in size. Some of the clearest learnings come from smaller, focused models like the Independence at Home Demonstration which tested home-based primary care for mobility limited beneficiaries. Congress deliberately limited the model’s size allowing for a better understanding of the mechanisms that has allowed the approach to continue to to show meaningful savings and quality improvements.

None of this should be taken as hard and fast rules but rather a starting point for CMMI to fundamentally rethink its role. The creation of CMMI was an important acknowledgement by Congress that government agencies need the space to test new approaches to fulfilling the spirit and mandate of statutory programs.

However, CMMI strayed from its mission. Rather than operating as a research driven laboratory for payment innovations, it has become an engine for too many complex programs that fail to deliver insights. Urgent reform is needed to limit program scope, direct funds to on the ground clinicians, and realign its strategy with the core pillars of the Medicare and Medicaid programs. If done right, CMMI can demonstrate that the idea of testing new approaches to administering government programs can be a path to improved efficiency.

Ankit Patel was formerly a Senior Advisor at the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation.

NK note and parting thoughts

Yeah…what he said.

Thinkbois out,

Ankit Patel aka. “But what about FFS?” and Nikhil aka. “Oh FFS, who cares”

P.S. If you have a different policy perspective you think would be interesting to write about, let me know!

Twitter: @nikillinit

IG: @outofpockethealth

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.