How Health Data Gets Sold: Moving From Third-Party to First-Party

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveHealthcare 101 Crash Course

%2520(1).gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

The two paths of health data acquisition

If you look at how health data is being brokered today, there are two sides.

On one side you have companies creating totally new ways to monetize patient data without patient involvement. The market for patient data brokered by a third-party is massive, but basically doesn’t involve any awareness from the patients and uses de-identified data.

On the other side you slowly have an ecosystem built that allows patients to finally get their own data out of the health system and authorize the third-parties they want to give it to. This is more of a first-party healthcare data system.

To date, companies have relied on the former to get data because it’s easier. But I think there are reasons to believe companies will want to get that data from patients directly in the future.

Background: How Data Commercialization Works Today

Whenever you use any sort of healthcare service, it generates some data about you. You might go to a hospital and generate a lot of data in their EHR. You might get imaging done at a radiology group. You might use your insurance and generate a claim.

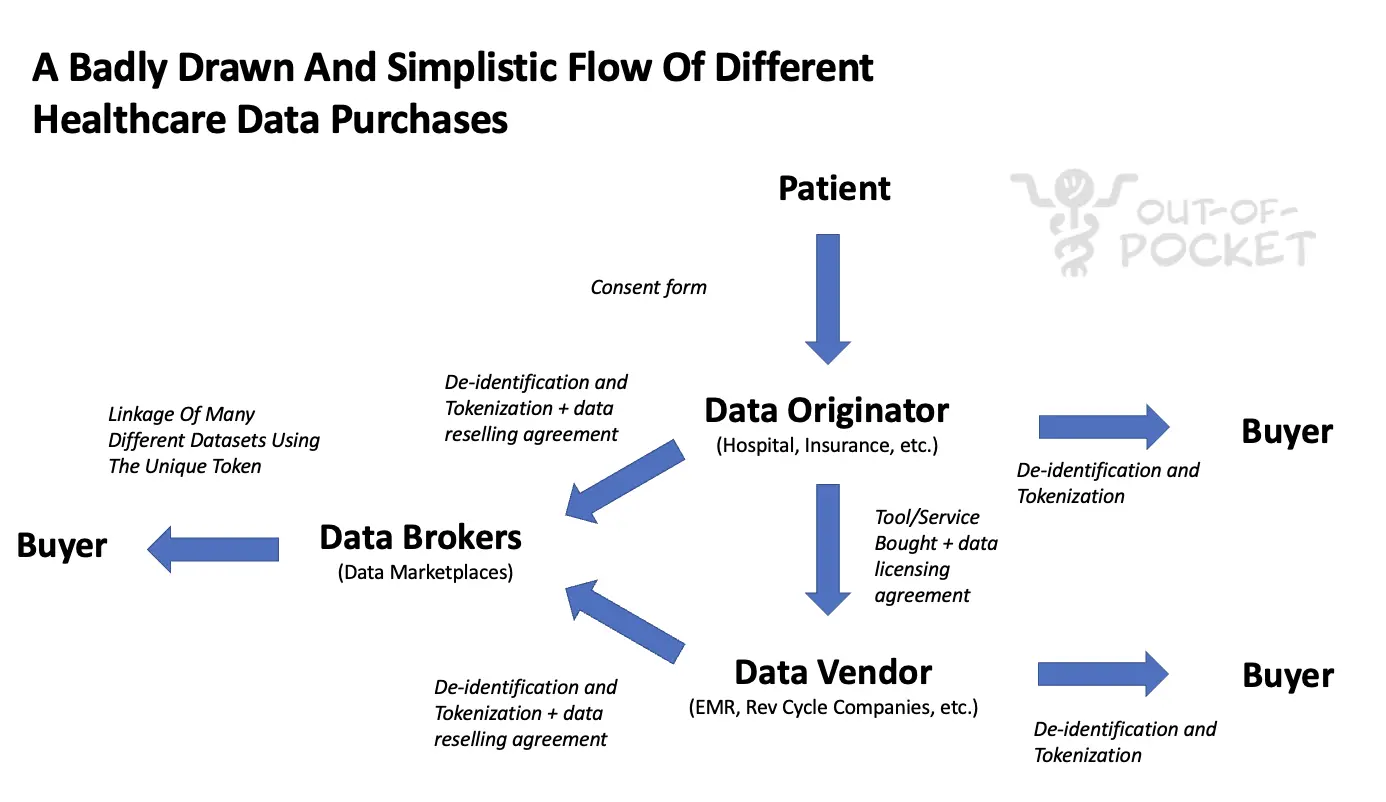

This is valuable stuff. That good good. So behind the scenes it gets monetized/commercialized. Here is my very not nuanced flow of how this might happen with terms I sort of made-up or have heard thrown around at some point.

A patient goes to get something done and signs a consent form. Sometimes that consent form has something in it that allows your data to be shared in a de-identified way with third-parties. A lot of times this consent won’t even technically be necessary if your data is sufficiently de-identified.

The patient might see a doctor, file an insurance claim, etc. That hospital is the originator of that data because it’s creating it. While typically these hospitals have handed that de-identified data to third-parties to sell, these data originators are now realizing how much value there is in the data they’re creating and investing in cleaning + enriching that data and setting up third-party companies to sell it. 14 health systems including Tenet and Northwell have banded together to create Truveta so they can structure and sell data (which just raised $95M). Blue Health Intelligence has aggregated claims data from the different Blue Cross plans. Buying data from these originators is generally cheaper but smaller scale, usually messier, and would require individual licensing.

Another way originators are commercializing their valuable data is to use the identifiable data to create new products. This is useful for areas that need really deep and annotated datasets or need to be embedded into current workflows and have all of the patient data pass through it. Hospitals are creating and spinning out their own companies. Some examples:

- Sema4 spun out Mt. Sinai using its genetics data and recently SPAC’d

- Paige AI spun out of Memorial Sloan Kettering using its annotated pathology data

- Mayo Clinic is spinning out two remote patient monitoring/ECG algorithm companies

Data vendors are usually companies that sell some sort of service to the originators and generate data “exhaust” as a result. This might be clearinghouses that actually process the claims, EMRs that actually hold the data, etc. These companies usually invest in structuring the data anyway as part of the product they’re selling (e.g. providing benchmarking services to the originators). They will also sell de-identified versions of this data to buyers. Epic has built Cosmos, a massive database of de-identified patient records for a wide array of planned use cases. Change Healthcare is a clearinghouse with lots of structured claims data. The aggregators usually have more data that’s structured and enriched + aggregators also have licensing + data rights from the originators they’ve pre-negotiated at a larger scale (meaning fewer contracts for buyers to manage). However, this will be more expensive and is typically good for one data “type” each (e.g. just claims data).

Then there are data brokers. These are usually companies that pre-negotiate sales agreements with originators and aggregators to sell their de-identified data. These data brokers usually provide important services to companies to make their data commercially viable: stripping the data of identifiers, “tokenizing” the data so you know it’s the same patient across datasets even if you don’t know who the patient is, and standardizing the data so it’s queryable. Companies like Datavant and Healthverity would be considered data brokers. Buying data at this level usually gives you the most types of data + it’s queryable + you can use the tokenization on your own internal data to connect it to matching tokens in other datasets. This will most likely be more expensive on a per record basis, but you can usually get way more granular (e.g. querying for patients with a specific ICD-10 code in the claim AND “X” lab value AND “Y” prescription drug at a specific dosage).

Beyond this, there are companies like Komodo Health that wholesale acquire and package data from all of these different entities then create totally new products for their end users. Komodo has pre-built dashboards/products that use this data to do things like figure out site selection or protocol design for clinical trials, patient journey mapping, identifying providers of high importance if you’re a medical science liaison, population health stuff, etc. You can almost think of companies like this as outsourced data science departments to build products out of the morass of data.

De-identification and tokenization is really the key here and one of the things that makes this entire ecosystem possible. This is the process of replacing sensitive identifiable information with a non-sensitive but unique replacement (thank you Wikipedia article on tokenization). Datavant bought a company called Universal Patient Key to do this. Using tokenization you can link datasets together and, with a very high level of certainty, know it’s the same patient through all of the datasets. Since we don’t have patient IDs, we have to resort to this (which has the kicker of being HIPAA compliant without needing explicit consent from the patient).

Turns out we had interoperability the whole time! It was just happening in the back end where it’s way more lucrative.

Shifting From Third-Party To Getting Data From Patients Directly

The reality is that in order to build great new products in healthcare, having access to patient data is *Khaled voice* major key. This is true for companies that require training data to build new tools and therapeutics, companies that want to conduct large scale research, companies that want to model out trends happening in the world today, and more. Currently the best way to get data at scale with all the features you’d want in the dataset is through third-parties.

However, I think companies will want to move more towards a first-party data collection system where they get the data directly from consenting patients. Here are some of the reasons I think that will happen.

The Infrastructure for Sending Data Directly Is Being Built

The new rules around information blocking create standards on what data should be available, type of format they should be, and how APIs can be built to access this data. This makes it much easier for patients to give access to any third-party they want (well...eventually).

These rules are evolving in terms of what data types need to be included and it might be a while before all of this is usable, but the rails are being built to make it easier to transport different types of health data if a patient gives authorization. This will make data hoarding less defensible over time as it becomes more freely accessible + it’ll be easier to distribute other types of data to developers building on top of these rails easily.

HIPAA and Consumer Data Sentiment

I think most people agree that HIPAA just isn’t really cutting it anymore when it comes to data privacy. One big part of HIPAA is making sure that if datasets are being sold or used without patient consent then they have to be de-identified.

The problem is that our re-identification techniques have gotten better, reidentification is easier with more data linked together, and individual datasets are increasingly more personal. Genetic data is impossible to completely de-identify. You can even identify a unique individual out of 100M people by using 6 days worth of step counting from their Fitbit. Grocery store data is included as an available option for many third-party health data brokers, and let’s just say it wouldn’t be hard to re-identify me in a group for that.

It feels like the winds are blowing in the direction of putting much tougher regulation around how brokering of personal data actually works if you look at Cambridge Analytica, GDPR, and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). A less than fun fact, nonprofits are exempt from the CCPA which adds further fuel to my argument that we should very seriously re-evaluate hospitals' non-profit status.

I’d be willing to bet that these kinds of de-identified third-party sales will be much more difficult in the future if regulation keeps trending in this direction. Especially as the data used in healthcare becomes more personal and inevitably identifiable. And if social media companies keep bringing the spotlight to user data by doing more sus things.

Extremely Personal Non-Healthcare Data

We generate so much data now at an individual level that we’re slowly starting to find out how different, esoteric datasets can actually be indicators of our health.

- Here’s a paper that used ML to monitor Facebook posts and uploaded images in order to identify people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and mood disorders a year before they had their first psychiatric hospitalization (with signals more pronounced leading up to the hospitalization).

- This study looked at consumer credit reports and found an association between missing credit card payments and developing Alzheimer’s and related dementia (which could be noticed up to 6 years in advance of an actual diagnosis).

- Vocalis Health, Aural Analytics, and Sonde Health are just some companies trying to use voice data to measure disease progression or diagnose a disease.

- Think about all the data that was used in pandemic response like bluetooth/location data for contact tracing. We can use that data to confirm what we already know - Union Pool is a super spreader event (not just for COVID).

This diagram from this 2014 paper is still chaotic good in showing all the different types of data with potentially rich information about our health, where that data is located (inside and outside of the healthcare system), and if it’s structured.

What’s important about these new kinds of datasets is they’re both extremely personal/sensitive AND exist outside of the current healthcare system. If you believe having access to this data is going to become increasingly important in healthcare decision making, then it’s going to require patients to give you authorization to use it. Coincidentally, there are also new APIs being made available to make it easy for consumers to give that data upon authorization (e.g. Plaid for your financial data).

Tangentially related, but if you want to study how these different data sources coincided with disease progression, it might actually make more sense to get this data from patients posthumously when they’re more willing to give it. Maybe “donating my data to science” is the new “donating my body to science” and data should actually be included in wills.

Data-Sharing Norms and Research

Speaking of research, in the last few years we’ve seen the proliferation of decentralized trials and large scale real-world research studies. Being a part of a study requires patients to give consent to share data directly and include larger parts of the patient population.

First, it’s very likely we’ll see lots of decentralized trials spin up thanks to new infrastructure to spin up large scale trials without physical sites or complex enrollment requirements. Apple’s ResearchKit has made it easy to spin up studies using the hardware in Apple products and Google launched their own version for Android. Lots of decentralized trial companies have raised in the last year thanks to COVID tailwinds (Science37, Medable) and large CROs like PRA are running totally decentralized trials too.

Also interesting is the increased normalization of healthy people joining studies. Evidation was probably one of the earliest in the space with its Achievement app which lets people earn money by giving their data, contributing it to research, and taking part in future research that might be more relevant/specific to their disease area. Even pre-COVID, we saw large biobank projects like All of Us or Verily’s Project Baseline aim to track a lot of data from a massive set of patients of different health statuses and age groups to see how they progress over time. There have also been a proliferation of studies during COVID that have used different sensors/wearables from users to potentially detect COVID early on.

As these trials become more popular and enroll more people, you’ll have more people participating in studies where they’re actively authorizing and giving data themselves. Some benefits of this:

- Without the need for sites + making research accessible from everyday hardware, you can enroll much larger scales of trials. The MyHeartCounts study looked at sleep, physical activity, and cardiovascular risk for 50,000 people in 2019.

- By using more flexible and simple informed consent, it’s easier to funnel patients to other follow-up studies that might be relevant to them.

- As I wrote about with the Fitbit Heart Study, you can get retrospective data that was already being passively collected before they actually consent to the study (so you’ll have a baseline to compare results to). The Fitbit study used data 30 days before the participants signed the consent, which is impossible to do without a prior relationship with the participant.

- If you enroll patients when they’re healthy, you get much better disease progression data that shows how their disease pathology actually developed. Plus, you have access to the patients when they’re first diagnosed, which is important if you’re trying to guide the patient to different available care pathways (e.g. some clinical trials will not be available to them if they jump straight into the “treatment as usual” immediately).

- By having first-party consent, you can more easily ask for more data as the trial continues since you have direct access to patients. This is especially important if you’re running some sort of adaptive trial design which changes over the course of research.

I think being a part of studies will become increasingly more normal for everyday people, and first party data will provide a great complement or even replacement for third-party data depending on how niche/deep the data required is. It might...even be a flex to say you’re a part of research???

Dataset Diversity

Finally, I think we’re going to start to see more dataset diversity requirements for companies.

There is an increasing amount of awareness over the biases that come from training data that’s not representative of the general population. There are lots of examples of racial bias emerging in different software. There are also biases in training data on specific care settings - e.g. larger hospitals and academic medical centers are more likely to have the means of commercializing their data but also have a skewed patient population that gets care there. Most healthcare algorithms train on data from Massachusetts, New York, and California with relatively little representation from other states.

The FDA is starting to take notice of this and it seems to have come up in several discussions around Software-as-a-Medical-Device committees. I wouldn’t be surprised if in the future, the diversity of populations in the training data becomes a requirement in some capacity.

“Efforts to offset algorithmic bias and ensure robustness will draw on collaborative regulatory science research methods to evaluate AI/ML software. In particular, the FDA noted that AI/ML software uses historic datasets that might reflect data variations along racial, ethnic, and socio-economic status lines. The agency emphasized the importance of addressing those inherent biases to ensure medical devices are well suited for a racially and ethnically diverse patient population.”

By getting data authorized from patients directly, companies are more likely to have a diverse population represented in training data. The MyHeartCounts study had participation from every state except Maryland (there’s always one “contrarian”). While the racial representation leaves something to be desired, the size of the study is so large that you probably have enough people in any given demographic to do a subpopulation analysis.

Dataset diversity is also useful not just to get a more representative sample, but also reduces dependencies on a concentrated set of data providers. If you are dependent on getting your data from a small handful of third-parties, then you have a potential concentration risk if any of them shut off their data exhaust for some reason.

The dependency also means you have to hope that whoever is creating the data is capturing whatever fields you want and structuring it in the way you want. If you care about getting data on a patient’s race for example, what are you going to do about the fact that many of the EMRs don’t capture that data in the first place?

Getting data directly from patients can help reduce the customer concentration risk, better control the type of data you’re capturing based on your needs, and give a higher likelihood of getting a representative sample in your training data.

Parting Thoughts

I don’t think third-party data sales will go away any time soon, if at all. But I think companies should explore first-party data capture as a strategy going forward.

I think one of the open questions is how consents would work for a system reliant on first-party data capture. GDPR has turned the internet into a vast hellscape of each website asking you about your cookie preference. Doing that for first-party data capture seems infeasible.

You’d probably need to create some overarching consent that travels with your data and asks for follow up consents from specific tools/studies that want extra data. I don’t totally know how you would solve this but I’m sure I’ll get some replies from blockchain aficionados about how this is the perfect use case.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “First-Party > Third-Party > Aaron’s House Party”

Twitter: @nikillinit

Thanks to Malay Gandhi and Anonymous for reading drafts of this post

---

{{sub-form}}

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.