The Ins-and-Outs of Cancer Care Navigators With Laura Stratte

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveHealthcare 101 Crash Course

%2520(1).gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Today I’m interviewing Laura Stratte, a registered nurse, 12-year breast cancer survivor, and until recently, breast cancer care navigator. Laura is now a program & ops manager with Elektra Health, a women's health startup in the menopause space.

We discuss:

- The role of a cancer care navigator and what their tools and processes look like

- The journey of a breast cancer patient and issues that arise along the way

- Second opinions, clinical trials, and patient communication generally

- How COVID might change breast cancer care in the future

What's your background, current role, and the latest cool healthcare project you worked on?

My background is varied - first degree in fine art, realized it’s really hard to pay rent when you’re an artist, went into nonprofit administration for several years, then actually got to use my degree with a small necktie company - it was a very small operation so we all did everything, marketing, shipping, customer service, design. I finally made my way to nursing school and have been an RN for 11 years - I worked in informatics during a massive migration from mostly-paper to mostly-EHR in 2010-2012 and moved into oncology where I’ve been ever since. I was diagnosed with breast cancer while in nursing school, and after that I knew I wanted to go into oncology nursing and navigation, and I ended up working at the hospital system and cancer program where I was treated.

The latest project I’ve been working on is starting to build a comprehensive survivorship program for a multi-site site cancer program, each site with its own org structure and culture. Survivorship care has many different models, but in essence, it’s addressing the long and late term side effects that cancer and cancer treatment cause (physical, emotional, financial, sexual, practical, etc.), health promotion and fostering healthy lifestyles, and ensuring and coordinating appropriate follow up for cancer screening and surveillance. COVID derailed it for a time but now we are trying to get things moving again, but I’m excited about the changes that are happening in healthcare right now because of COVID, especially the opportunities that telehealth offers.

Can you walk me through a step by step of what happens when a patient comes in for their first treatment in chemo or radiation therapy? What are common issues that come up?

The cancer care journey and all of the issues that go along with it start well before treatment - it really starts with the screening/work up which leads to the diagnosis. It can vary by cancer type and the specific situation, but the route often looks like: screening (maybe) > diagnostic work-up (imaging, labs, biopsy) > additional post-diagnosis imaging > MD consult > perhaps more imaging/tests > development of treatment plan > start treatment. So there is a lot of room for issues to pop up. There are barriers to care from the healthcare and institution side (insurance or lack thereof, cost of care, prior authorizations, scheduling issues with scans/surgeries) and from the patient side (transportation, communication, employment, mental health issues, co-morbidities, support, financial status, etc.).

I’ll cover what happens with breast cancer patients from the point of diagnosis, which is where the navigators in my center step in, and I’ll just deal with this small part.

Step 1: Post-diagnosis/pre-consult testing

Immediately after diagnosis, many patients will get a breast MRI and ideally, this done before step 2 below. The MRI takes a closer look at the breasts and may lead to additional biopsies.

- Scheduling and/or insurance authorization can be issues here. Our weekly tumor board (meeting where the whole team of players - radiology, pathology, physicians, genetics, nurses, rehab, research - review cases and discuss treatment options), and new patient consults are on Wednesday and sometimes there are no open MRI slots before that Wednesday clinic, or we can’t get it approved before then, so the MRI doesn’t happen.

- We’ve gotten much better at the insurance prior auths over the years - we now have a whole department of people whose job it is to manage it - it used to be the RNs. For the MRI openings, this is a recurring issue that gets resolved, pops back up again, etc.

- Here we need to play a delicate balance - it’s not ideal for the patients to meet with the doctors without all of the information like the MRI - it’s frustrating for both sides not to have all of the info in that first conversation. But if we push back the appointment by another week, it’s really really hard for the patients to wait, and they may decide to go to another system that will get them in for the MRI first.

- Getting Her2neu ISH (in situ hybridization) testing back in time - (About 20% of breast cancers are Her2neu positive, which means they have extra proteins that promote cell growth - think cancer cells on steroids. We have drugs that specifically target Her2, so we test all invasive cancers for this). Some women will need to get this additional Her2neu testing done and this is a send out and can take around 5 days to get back. It’s best to have this back by the Wednesday clinic, but depending on the timing of the initial biopsy, it’s not possible, or there have been many periods where the outside lab gets really really slow in turnaround.

- Another delicate balance to play - Whether a patient is Her2neu negative or positive can have a big effect on the treatment discussion and treatment plan.

Step 2: Breast Multidisciplinary Clinic (MDC)

We have a weekly multidisciplinary clinic (MDC) that we hold weekly and we bring in all new patients from the week. At this appointment, they see their whole care team - surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, maybe plastic surgeon, and they’ll see our rehab therapist briefly for arm measurements and they’ll meet with the navigators as well. Most patients leave with a tentative treatment plan in place, with clear next steps.

- This 3-4 hour long mega appointment can be problematic for some - it can be tough for some patients or their support people to take time off of work (they need at least the whole morning off), arrange transportation, childcare, etc. Do we need to hook them up with their medicaid transportation benefit or do we need to use Lyft? Do we need to connect them with our social workers right away?

- This model can be simply overwhelming for some patients, especially if there are underlying anxiety or cognitive issues - and if known in advance, we try to change it up, so they may only see a single physician that day. But even without anxiety or other issues - it’s still a tough, long, grueling morning.

- MD scheduling can be an issue here. If the referred surgeon is on vacation, what do you do?

Step 3: Post-MDC testing/procedures

Often patients will need some additional testing done after review at tumor board and MDC before a treatment plan can be finalized or treatment can start. For example, staging scans might be ordered to see if the patient has metastatic disease - this can drastically change treatment. Other patients may need some pre-testing done in anticipation of treatment - for certain chemo regimens, you’ll need an echo to check heart function, you’ll need to get a port placed (done outpatient in interventional radiology). Some patients may need to get pre-op clearance from a cardiologist or primary care physician.

- These may require insurance prior auth, which always has the ability to hold things up.

- Again, we may be at the mercy of scheduling - PET, CT, etc may be booked for a week. IR might not have an opening. Some patients may not have a cardiologist or PCP - no one may have an opening for weeks, so this usually involves reaching out directly to MDs to see if they’d make room in their schedule.

- Again, patients may have significant barriers to take time off of work, with transportation. We do our best to bundle appointments so they are back to back, or at least on the same day but that’s not always possible.

Even before the patient comes in, navigators assess their barriers and try to get them connected with resources from the start. Transportation (social worker), insurance/charity care (financial advocate), and social services (social worker) are usually the first referrals we do.

Another common issue that pops up along the way is something that’s inherent to the cancer experience - the waiting, the uncertainty, the expectations vs reality, and the little surprises that pop up that can so easily throw things off, even if those little surprises are relatively insignificant. It’s hard to manage your emotions when you are teetering on the edge and that’s what you often feel like when you are diagnosed. Getting diagnosed with something like cancer and going through treatment is like adding a part-time job onto your life, one that you don’t have much control over. We are thrusting patients into this system that is super complex, often incredibly disjointed, usually last minute - this emotional element adds another layer of complexity and can be really challenging to manage both from the clinician and patient sides.

What software do you find yourself spending the most time and what's the most frustrating part/if you could wave a magic wand and fix one or two things, what would they be?

So much time is spent tracking patient status and patient data, and we don’t have any good tools to do so. The EHR is not a patient management system, and there are some navigation software systems out there but my health system hasn’t invested in them.

We’ve created our own systems to track patients as they progress so we can keep tabs on them - which often involves paper charts/binder, Google docs, and spreadsheets that we constantly update and work from. We are always looking at schedules, EHR, etc. to see when the patient has appointments, if they have appointments, etc, what this MD note said, etc. There’s a lot of double charting, redundancy, and time spent on manual look up and entry. And this need lasts after active treatment is completed - Did the patient come back in for their 6 month follow up? Did they get their follow up mammogram?

In addition to tracking patients to help manage them, we need to track patients for data - how long between diagnosis and MDC? What surgery did the surgeon recommend vs what did the patient elect - is there a trend? What chemo regimen was used? What about radiation protocol? Did the patient leave the system- if so, why? How many patients were diagnosed at stage III? Stage IV? In our center, all of this data is expected to be collected and reported as needed by the navigators - we do this all by spreadsheet.

A true patient management system would be the solution - We need a system with a patient dashboard, so we can see where the patient is in treatment, and what is going on with them, where we can get alerts for certain events or non-event (no shows), where we can track referrals to ancillary services, etc. and where we can query and report.

How do patients prefer communicating and what kinds of things are they typically asking/looking for from their navigator?

We usually communicate via phone but will use email and snail mail as well and for some conversations, it’s best to be in person so patients will often see if we’re available when they’re in the clinic, and vice versa.

Patients come to us for anything and everything. Navigators are often the one constant throughout the entirety of treatment, we are usually available (or they know we’ll call back soon), and we’re able to help with most things because we bridge so many different disciplines. Even once they get into chemo and radiation and we take a step back, we are often the ones they turn to first. Lots of calls about symptoms, appointments, looking for reassurance when they are in panic mode, asking for clarification about something they heard from their MD, their friend, online, etc. (especially in the beginning). Years after treatment, patients will still call us for all sorts of random reasons.

When I was diagnosed, I have to say I’m not sure I would have gotten through it all as easily as I did without my navigator - she was my rock, my constant, she would just make me feel better when I saw her. I was closer to her than to my doctors and really trusted her opinion.

How do you interact with the physicians/oncologists, etc.? Are they leaning on you for help in specific areas?

We work in a really strong team environment - for the most part, we trust and respect each other. We’re all jammed into one building, so we are constantly stopping by each other’s offices, or in the hall, we message and text.

The MDs rely on us to manage tumor board, make sure the initial clinic runs smoothly, make sure patients are prepped for that first clinic appointment so the patient isn’t hearing about the possibility of a mastectomy, or chemo, etc. for the first time from them, to help when there are patient issues, to get things scheduled, to make sure they have the proper records/results when the patient comes in, to step in if there are any issues with other departments, to remind them of things (for example - many patients elect not to do genetic testing right up front, but they want to do so at some point down the line - the navigator is the one that remembers to make sure the patients eventually gets to the genetic counselor).

Do you typically talk to patients about potential clinical trials? How do patients think about decisions around new treatments?

At our tumor board, research will screen patients and flag those that are eligible or potentially eligible for trials. I’ll talk to patients about it but very generally because our research RNs and coordinators do a really good job of getting in touch with patients and explaining it all. I’ve been a bit more looped into a few trials where I was involved in recruitment but they weren’t drug trials - I haven’t actually gotten a lot of questions about pharma trials since many are for the metastatic setting and I don’t work with that population. The discussions I have had about drug trials tend to be around the question “what if I participate and I don’t get the trial drug.”

When I do talk to patients, it’s more of a “clinical trial participation is good” pep talk and I stress how this is a way to help someone else down the line. We’re actually starting a clinical trial with people who declined participation, to learn more about why - not sure how accrual is going on that one but I suspect it’s challenging.

How/when do patients typically look for a second opinion? Is that common/is there something common between the patients that ask for one?

This is a super common question. In my experience, younger women tend to get second opinions, as do women with more complicated or advanced cases.

The main reasons people will ask are :

1) the patient’s friends or family are telling them to go see Dr. X at X system - sometimes they can really put a lot of pressure on the patient to do so - most of the time at my center, family/friends encourage them to go to the local academic medical center, and there’s definitely clout that comes along with being in an academic center vs community hospital,

2) that’s what they heard/read that you should always do

3) they don’t like what they hear (eg the doctor is recommending mastectomy or chemo, or something that the patient does not want to do)

4) they don’t like the doctors/our center for whatever reason

5) the doctor is giving them options between treatments - making that decision is really difficult for patients because you’re being asked to choose between two options you really know very little about,

6) the case is super complicated - in which cases MDs may actually suggest getting a second opinion.

Usually people will get second opinions right in the beginning, but I’ve also seen patients get them after surgery when there’s unexpected pathology (usually, the pathology proves worse disease than what was thought clinically.)

I always tell people that it’s never a bad idea to get a second opinion and I never discourage it. Some breast cancers are fairly cut and dry, however, so if their case is pretty straightforward, I tell patients that the second opinion is likely to be the same or very similar, so if you feel good about our team and what they are telling you, then it’s OK to not get one (some people need to hear that, especially if they have family telling them otherwise).

If the case is complicated, I may be a bit more encouraging, or even very directive.

Do you think there’s anything that changed during COVID regarding cancer care that will remain permanent once COVID is over?

Great question! The most obvious - virtual visits for appropriate appointment types and using more digital communication/education methods - the clinic is way too paper and phone call dependent and I think that there’s no going back.

Bishal Gywali wrote a great article about this in JAMA Oncology (he tweeted the article, otherwise it’s behind a paywall). His points about selecting higher quality/value treatments and addressing screening recommendations (this is a huge topic) are spot on. There’s still a lot to learn about how some of the adjustments made to date will affect outcomes, but it’s an important conversation we need to be having.

On a more granular level specifically within breast cancer care, I hope that neoadjuvant hormone therapy becomes more of a regular option for women who want to delay surgery for a bit due to life circumstances.

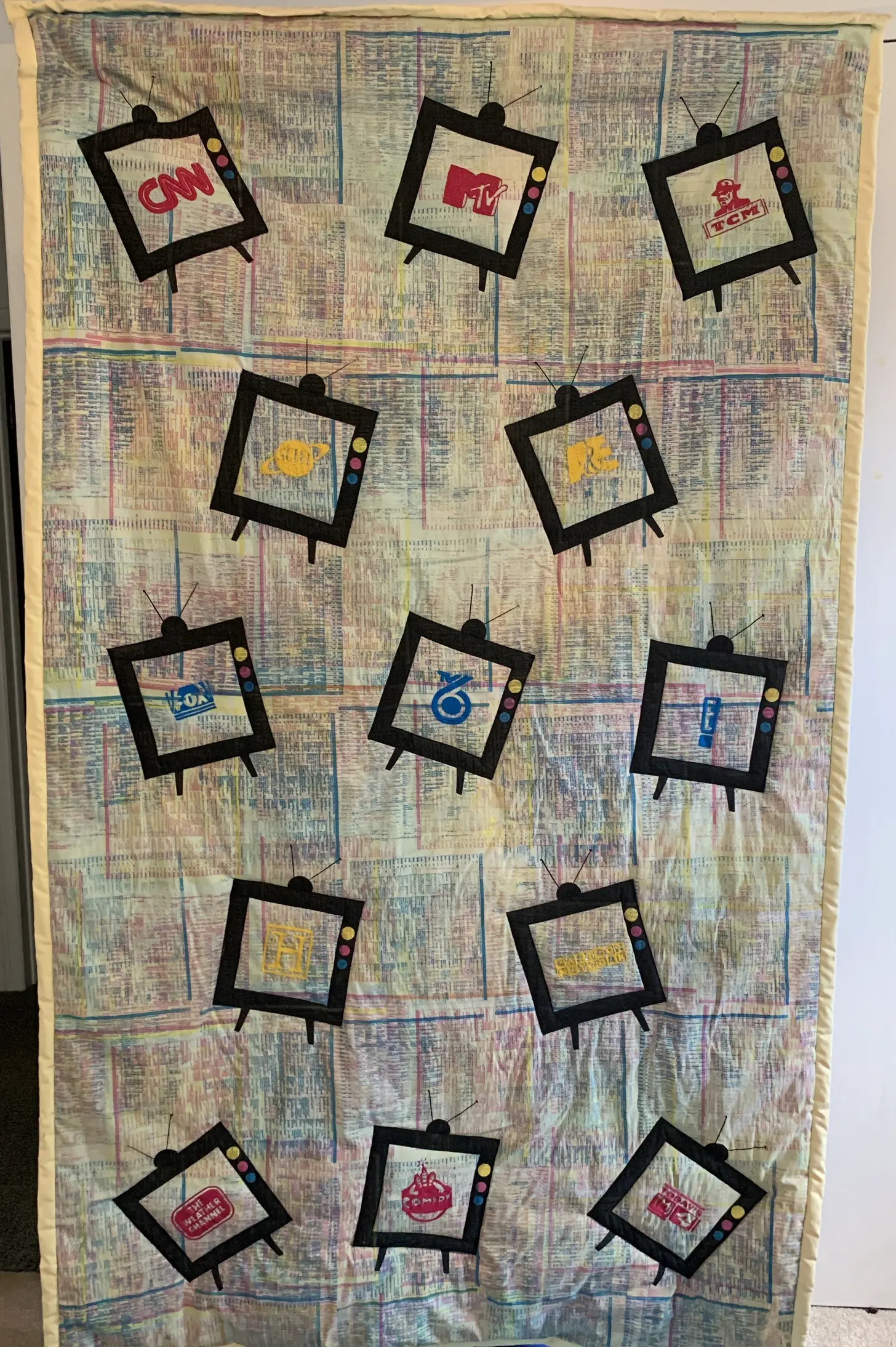

Bonus: If you went back to being an artist right now, what kind of art would you be making?

I’ll reframe this and tell you what type of artist I’d love to be: I’m obsessed with decorative arts and those artists/designers that touch the whole space - textile, furniture, houseware, architecture, etc. I’d be doing that and making pretty things and uncluttered spaces. Or I’d be embroidering, which is very old-ladyish of me but I get into the zone and it’s super relaxing, and I can do it while watching TV (my very favorite piece I’ve made is an embroidered quilt about TV because I love TV).

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “there’s probably opportunity to build care navigators for other diseases”

Twitter: @nikillinit

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.