Scheduling, Medicaid Opportunities, and Health MBAs with Sandy Varatharajah

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

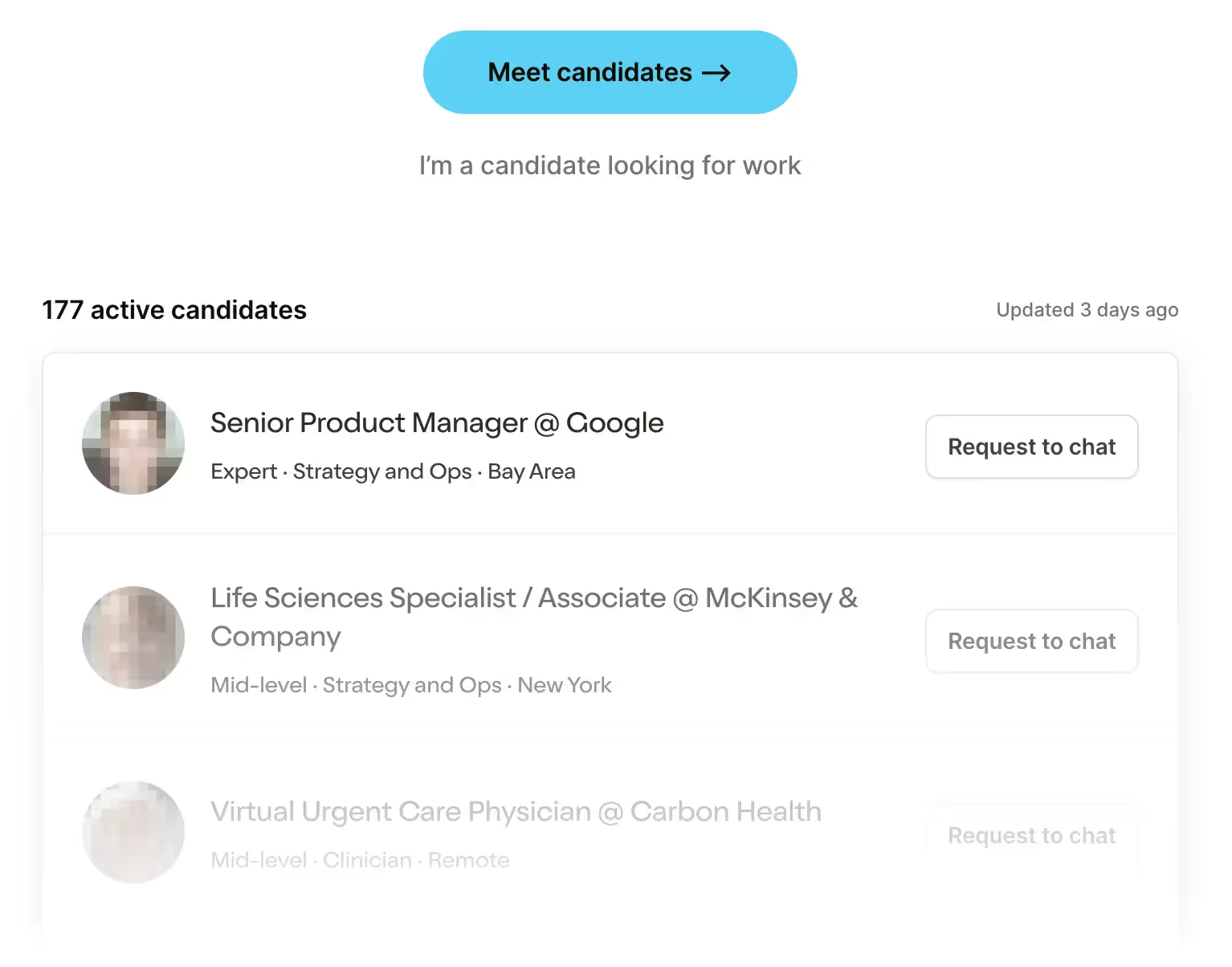

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveHealthcare 101 Crash Course

%2520(1).gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Today I’m interviewing Sandy Varatharajah. She’s worn hats all over the healthcare system (scheduling, Medicaid, care delivery, and more) and has taught me a ton about how healthcare works. She got tired of lecturing me on things, so I tricked her into lecturing all of you so I could still bother her with questions. She’ll be joining Oak Street Health this fall as a Director of Population Health.

We go over a ton of different topics:

- Why is scheduling such a shitshow in healthcare and what goes on behind the scenes to set up scheduling?

- Surprising facts about Medicaid and where opportunities exist in the space (PACE, C-SNP programs for kids, etc.)

- Section 1115 waivers, what they are, and why they’re important

- And more

1) What's your background, current role, and the latest cool healthcare project you worked on?

In past lives, I worked in product commercialization, strategy and operations roles at Zocdoc, Cityblock Health, and the Advisory Board Company, and stints in tech, venture capital, and early stage digital health companies focused on elder and value-based care. I just wrapped up my MBA at Wharton, and recently worked on a risk stratification project for a company focused on high-acuity long-term care patients.

2) Having looked a bit into the scheduling side, why is scheduling so much harder in healthcare than any other industry? And even when you schedule, why are doctors always late anyway?

There's so much underappreciated nuance that goes into provider scheduling logic across hundreds of different scheduling softwares. Restaurant tables have only a few booking categories (bar, indoor, outdoor), as do plane tickets (economy, economy+, business, first class). Each entity in these industries works off a unified software system for booking and management. This is not the case for doctor appointments.

When you schedule an appointment, office staff go through two decision trees. I’ll call them (A) validation and (B) slotting. The first is figuring out whether the patient should be seen by this practice at all: are they in-network, do they have an existing provider relationship, do they need prior auths or referrals, do we trust the patient has triaged themselves to the right specialty and visit reason? If "no" on the latter, the patient might require more time (rippling wait times for other patients) or less time (creating gaps in schedule that go unused, leading to lost revenue in a FFS world) than their visit guarantees.

The second is literally figuring out where to slot patients in. Providers have appointment blocks reserved for specific visit types, insurances, and even patient demographics. Each slot variant has a different duration. Some visits require services booked in tandem with a provider visit (e.g., counseling and nutritionist appts alongside a pediatric appt). Double booking is common because providers hedge their schedules against last-minute cancellations, reschedules and no-shows, which again equal lost revenue in a FFS world. Provider preferences dictate a lot of these practices: "I want to see Medicare Annual Wellness Visits on Tue/Wed mornings, but XYZ all day Thu/Fri." That latter human element is what makes it so difficult to automate scheduling at scale. Add on that there are 100s of possible EMR scheduling modules.

No wonder scheduling appointments on the phone takes patients dozens of minutes to hours. Then, the average wait time for a provider appt from search to booking is 3+ weeks. The frustrating thing is that providers often have near-term availability, but their scheduling systems are not set up to find the "next available" appt that is right for the patient. For example, Zocdoc automates this nuance across tens of thousands of doctors nationwide on disparate EMR systems - and surfaces near-term appts in real-time such that consumers never have to experience this backend complexity.

In a virtual care world, providers are shifting to on-demand telemedicine which offers flexibility to both them and patients. Companies like Wheel are distilling the complexity of managing hybrid synchronous, asynchronous, and remote patient monitoring modes of virtual care for providers. So, that adds a deeper layer of complexity to the scheduling problem, with more opportunity for companies.

3) What's the process of getting a schedule module set up for a doctor? What are common issues that might come up?

Most scheduling modules are available out of the box with a provider's EHR instance. Enabling patient self-scheduling varies by software. Some vendors like EPIC expose API endpoints that can be used for basic scheduling. Several vendors enable self-scheduling via patient portals. Other vendors might have less sophisticated systems, but you can build automation workarounds using different technologies, such as OCR.

Getting the scheduling module up and running is not the tough part. The tough part is defining what a provider feels comfortable exposing to patients for self-scheduling. Would you feel comfortable exposing your Google calendar for the world to book into? I would not. Providers feel similarly given the appointment computations named above. The margin of error is broader if a patient is self-scheduling versus an office manager, who might have worked with a provider closely for decades to understand their scheduling preferences. Many forward-thinking providers have entire workstreams dedicated to streamlining possible visit types. But this cultural barrier remains - and again highlights the human element in scheduling complexity.

Another consideration is duplicate patient records. When a patient self-schedules, there are backend actions to ensure that appointment is booked with the right patient record. This process gets tricky if there are multiple patient records that might match the appointment. Duplicate records are a much larger issue than self-scheduling, though - implications such as inappropriate order entry, missing patient medical history, and denied claims, can increase net healthcare spend.

4) Switching gears to chat about your time at Cityblock. I think there's always this question about where tech/software actually plays a role in these tech-enabled services companies. Do you have any good examples you can share about where tech played some important role in the business or managing patient care?

I'll highlight one here:

- Integrating risk stratification into care planning and delivery: using near-real-time feeds where possible for pooling data from disparate sources (e.g., EMRs, labs, PBMs, claims, patient self-reported assessments) and generating acuity scores for patients. Then, drive actual care plan suggestions based on those acuity scores by domain. For example, someone with high acuity food insecurity might need more help on their SNAP applications - and this would appear in the care team's Commons interface as a suggested task. Alternatively, a patient may have a high acuity medical domain driven by high HbA1c levels - they may have an entire diabetes care plan suggested to them. Too often the risk stratification programs exist separately from day-to-day care and task management - Cityblock integrated both domains via tech. If you haven’t read it yet, Not Boring did a great recent feature on Cityblock explaining this vertical integration via tech (and the hard work of the incredible, inspiring humans on the Cityblock team).

5) Any surprising facts about Medicaid that you learned or common misconceptions about Medicaid you frequently hear?

- Surprising: That dual-eligibles drive a disproportionate amount of spend for both Medicare and Medicaid and most beneficiaries’ benefits are covered under integrated care or risk-bearing agreements. So-called “duals” must navigate two programs: Medicare for drug coverage, acute care, and preventative/primary care, and Medicaid for behavioral health, cost-sharing/Medicare premiums, and long-term services and supports (LTSS). The lack of integration between the two programs leads to fragmented care, higher costs, and poorer outcomes for this population. Few startups are actively targeting this population and integration problem specifically, and if they do, most target MA patients and are starting to move to adjacent lines of business with duals. There have been strides for this population - e.g., growing enrollment in dual-eligible special needs plans and PACE. Last year, MACPAC released an excellent summary report of the context behind duals and potential integrated care programs, and policy recommendations to better integrate care.

- Misconception #1: Medicaid is a welfare program for people who don't work. Actually, the majority of Medicaid adult beneficiaries who don’t face barriers to work (non-dual, non-SSI, nonelderly) work, but don't receive health insurance through their employer(s), or find private exchange plans still prohibitively expensive. KFF has a great report on the intersection of work and Medicaid enrollment worth reading to debunk this myth, though the pandemic disproportionately affected income security (and risk of contracting COVID-19) across these populations, especially those working in food/service industries.

- Misconception #2: Medicaid encourages states to overspend on healthcare. It's true that Medicaid is often the first or second line item in states' budgets, but for that very reason, most states (red, blue, and purple) have transitioned to managed care programs to cap Medicaid spending. Also, unlike the federal government, most states must balance their budgets annually, so they are incentivized to avoid spending beyond their means. Finally, Medicaid expansion has been shown to reduce net healthcare spend on traditional Medicaid programs. Most states have flexibility in determining optional services to cover - depending on which services (e.g., non-emergency medical transportation or NEMT), this can save a lot of downstream high-cost, acute care spending.

Note: Pandemic-related unemployment is driving up Medicaid enrollment/spend and threatening state budget shortfalls. On the bright side, some efforts are underway to relieve pressure on states, like increased FMAP rates, while also improving beneficiary enrollment processes despite the increased incurred costs. On the other hand, several states are planning to introduce cost containment strategies (like downward managed care rate adjustments and benefit restrictions, or accelerating value-based care).

6) If I was planning to start a company targeting the Medicaid population today - where do you think the untapped opportunities are that I should be looking more deeply into?

Two specifically that I am passionate about revolve around two specific vulnerable populations: patients qualifying for PACE, and children with special health care needs. If you're interested in reading about more opportunities in Medicaid, Amol Navathe, Bob Kocher, Julian Harris, and other notable Medicaid leaders did a deep dive into opportunities in Health Affairs earlier this year.

(A) Full-stack, tech-enabled PACE:

Background: PACE is the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly that evolved from a program in the 1970s in the Chinatown-North Beach community of SF. Today, it enrolls people who are (a) aged 55+, (b) mostly dual-eligible beneficiaries ("duals") who skew older/low-income with high rates of chronic illness, mental health diagnoses, etc, and (c) demonstrate a need for a level of institutional long-term care (like at nursing homes, aka skilled nursing facilities or "SNFs"). Their care is financed dually by Medicare and Medicaid via capitated payments for medical services. The problem is that there are only ~54K benes enrolled in PACE nationwide across 272 centers in 31 states. Compare that with ~12M duals nationally, about half of which use long-term care. This is mainly due to lack of program awareness, eligibility/application barriers leading to months-long processing (in some areas, 9 months), and low center profitability. There was a great NYT feature back in 2016 when PACE was a hot topic for public and private investors, but progress since then has lagged. Here’s a nice summary from Dan O’Neill from the lens of InnovAge’s recent IPO.

Opportunity: Create a tech-enabled services PACE company that manages enrollment to care delivery end-to-end. There are a few venture-backed players in this space: ConcertoCare, Welbe, Edenbridge, and a host of PE-backed cos. InnovAge recently went public. Another managed care/risk-bearing tech-enabled services company could become accredited through PACE, but (a) it’s hard as there is a high regulatory bar to become a payer organization, and even harder to get relevant state/federal credentialing, and (b) pursuing PACE becomes an issue of focus - it’s much easier to acquire or start a company de novo. While the fixed costs to start a program are high, technology can help centers reach breakeven/profitability sooner (e.g., creating models for staffing based on patient acuity, creating smart care plans, creating economies of scale for a community-dwelling population).

[NK note: from Innovage’s S-1, to give a sense of the numbers]

(B) Care delivery focused on children, especially those with special health care needs:

Background: Special needs plans (SNPs) are funded by CMS for duals (D-SNPs), those with severe/disabling chronic conditions (C-SNPs), and institutional care (I-SNPs). The historical purpose is to create a narrower risk pool for higher needs populations and provide higher levels of guidance/care (e.g., drug formularies, provider choices, specific benefits). These are targeted largely at populations aged 65+.

Opportunity: Children have special health care needs too - especially those insured under Medicaid and CHIP versus private insurance. A 2019 KFF report outlined that about 13.3M children have special healthcare needs, i.e., need long-term care due to intellectual/developmental disabilities, physical disabilities, and/or mental health disabilities. Medicaid and CHIP cover about half of these children either as primary or supplemental insurance, and these children come from primarily lower-income, racialized communities. While we've solved for gaps in coverage for these children, we haven't solved for actually improving care for these children:

- Four in ten Medicaid/CHIP children with special needs have 4+ chronic conditions, are more likely to have their education impacted (days missed) by their health status compared with commercially insured children, and are from families that may have to work less to devote time to their child's health needs.

- Add onto that the impact of school closures across much of the country for over a year during the pandemic: loss of in person education, increasing hunger rates from lack of school meals, social isolation, more closely witnessing caregivers’ personal/economic loss, etc.

- For CHIP specifically, well child visit rates across the U.S. hover around 70% in the first 6 years of life then drop to 50% ages 12-21. Dental service rates for ages 1-20 are around 49%.

I think there's an opportunity to create an integrated financing/care delivery mechanism for children with special needs, and partner with managed care plans to identify/attribute children to the care model. Create culturally appropriate and kid friendly content, and a health coach/mentor to help guide them through their (and potentially their caregivers') health choices. Co-locate with centers of community, like schools. Finally, CHIP has been notoriously bipartisan and successful in financing care for our most vulnerable children, so I'd think this kind of model would face fewer political barriers. Many habits/lasting health literacy may be developed before the age of 18, so it should be important to focus on rising risk populations even pre-adulthood. If further Medicaid expansion is on the horizon under the Biden Administration, I'd hope to see more reforms focused on (pre)adolescence.

7) We've talked a bit about section 1115 waivers - can you give a TLDR on what they are and what some of the cool experiments you've seen that utilize them are?

TL;DR: Medicaid is funded by both the federal and a state's own government. If states want to use federal funding towards Medicaid programs that this funding doesn't cover, states can apply for section 1115 waivers. This can lead to experimentation that expands access to care via services that aren’t traditionally reimbursed, OR to impose restrictions that aren't explicitly forbidden by the federal government (e.g., some states use these waivers to impose onerous work requirements for Medicaid benes). Today, most states use these waivers for long-term care, eligibility/enrollment changes, and behavioral health. We're starting to see more programs focused on SDoH and other domains. MACPAC and KFF have great history summaries here.

While many 1115 demonstrations have come and gone, I think these waivers can signal priorities for an Administration in restructuring Medicaid benefits and eligibility. During the Trump Administration, these waiver authorities were heavily focused on work requirements. However, early in the Biden Administration, federal officials rescinded authorities for work requirements in states where these were previously granted (some of which were previously on the docket for SCOTUS review in Arkansas and New Hampshire). It will be interesting to see what new waivers the administration approves as it, in parallel, potentially expands Medicaid. KFF is tracking pending and approved Section 1115 waivers here.

Bonus Question - You recently graduated from Wharton’s MBA program with a major in Healthcare Management (HCM). For people thinking about getting a healthcare-focused MBA, any advice to help them figure out if it’s worth it for them?

I’m biased, but I loved my Wharton healthcare experience! The heuristic I offer to folks going through this decision is to pursue the option that maximizes optionality. Obviously this is a personal and expensive decision, but for me at least, the MBA:

- Helped me calibrate on my career interests in a condensed, risk-free timeline. I had headspace for two years to try out many internships across different roles in healthcare services, rather than having to pivot jobs every two years. I don’t believe in 5-year plans, and a career is lifelong with potentially many pivots -- but to have this focus and intentionality now vs. later will pay early dividends professionally. If you do an MBA, I’d recommend immersing yourself in different professional experiences and communities.

- Concentrated a professional and geographic network of people interested not only in healthcare services and digital health like me, but also in biopharma, medical devices, payor/provider, physician MD/MBAs, and policy work. These folks really did challenge my perspective and cover my blind spots with arguments and sub-sectors I hadn’t been familiar with before. I got very close to my peers and have always received a response to a cold email to a Wharton HCM alum.

Note: I actually think there’s room to disrupt “the MBA model” via this lever. Nikhil is one of the only people I know doing this well via Out-Of-Pocket: creating intimate spaces where people across companies, roles and sectors can have open debate, moonshot discussions, accountability through assignments, and cheerleading through professional and personal milestones. It’s a lot of work, but it pays off in the form of closer personal and professional connection. I’m a part of dozens of healthcare Slack communities with upwards of thousands of members, but where I can count on two hands the number of people who meaningfully contribute to discussion. That isn’t substantive community building or value-adding IMO.

- Offered social capital that -- as a woman and a person of color -- lent credibility in spaces, especially in healthcare, where few people look like me.

[NK note: Accidentally disrupting MBAs is the greatest possible compliment I’ve ever received. You can apply to join the crew here, it’s due 6/27!]

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “Rain drop, Zocdoc”

Twitter: @nikillinit

IG: @outofpockethealth

---

{{sub-form}}

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.