Ins and Outs of Fundraising Today

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

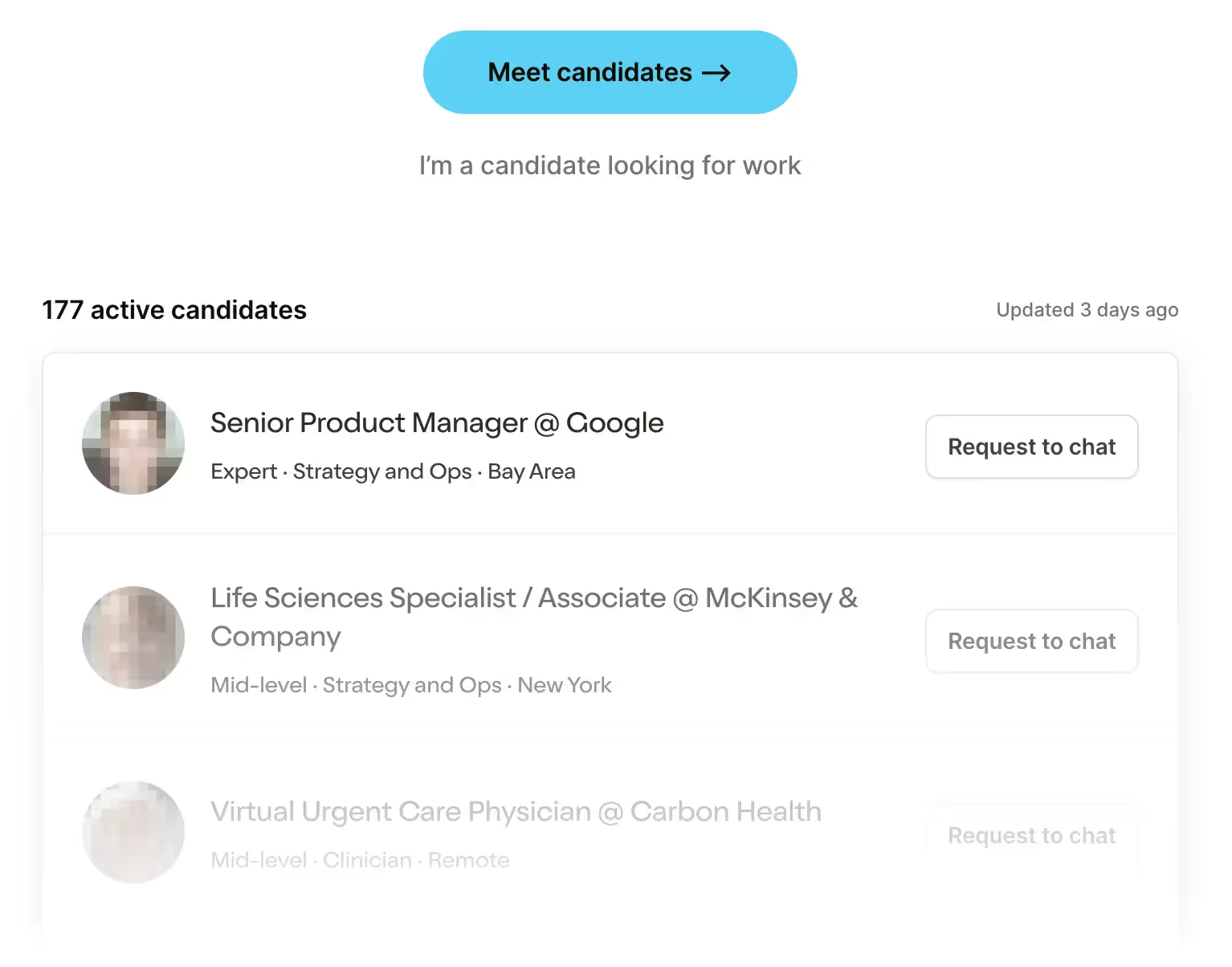

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveIntro to Revenue Cycle Management: Fundamentals for Digital Health

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Recently I did an interview with Seth Joseph for his piece about the current digital health funding environment. I thought it might be useful to expand some of the thoughts and jot down some very disjointed observations I’ve seen sitting on the investor side of the table, a new area for me.

For context, I’ve been around healthcare startups and investors for about 5 years and have been angel investing/scout investing in healthcare startups for about a year and a half. So with that said I have to give some massive grains of salt:

- Most investors don’t know if they’re any good for like 8-10 years, and usually more. I have no idea if anything I’m doing is working or not because I’ve been doing it for 1.5 years.

- I personally invest almost exclusively in pre-seed and seed stage companies, but have participated in some syndicates that do later stage investing and generally swap notes/stories with later stage investors.

- Angel and scout investing is very different from venture investing because you don’t lead or set terms + there’s less involvement in things like follow-on investing, board seats, etc.

- Investing is a side hobby for me, so I see a very specific sliver of deals because I just don’t have the time to look at every single one. This entire post is just the observations from my very limited lens.

- This has to be one of the weirdest markets ever to just get started investing because of how much money is currently in the ecosystem + low interest rates + COVID = valuation discipline and processes are getting thrown out the window.

So with that said, here is a random smattering of observations after sitting on the investor side of the table for a bit. This stuff is new to me, so if you disagree or have seen otherwise, please let me know. Hopefully this gives founders some context on what happens on the investor side + realize that a lot of other companies are going through similar thought processes as them.

The Founder-Investor dynamics

I have a newfound appreciation and understanding of Founder-Investor dynamics. The overarching theme seems to be the fact that “in-demand” teams have demand from basically the entire venture ecosystem. This means that they wield a disproportionate amount of leverage + are optimizing for keeping their “in-demandness”. It’s like “The Bachelor/Bachelorette” in investing form, and also much less interesting. Some things I’ve seen manifest as a result:

- Generating enough heat to find a lead for the round is the #1 priority thing for a company at the early stages. There are lots of different ways to do this - finding smaller checks and advisors that provide credibility, making it seem like an investor is “finding” you and you’re under the radar, generating Twitter buzz, pretending like you’re not fundraising but are thinking about it in the future, pitching to less well-known venture firms first to practice/refine the pitch and get term sheets so it can seem oversubscribed before going to the tier 1 firms, etc. You’re trying to create some investor FOMO. However, it’s also clear that if a company loses heat in the fundraising process, it’s incredibly difficult to gain it back. VCs that tend to co-invest with each other share notes so if you’re approaching all of them and they’re all considering an investment, then one of them dropping will significantly drop the heat in your other conversations. For what it’s worth I think this dynamic sort of sucks and venture investors who have independent conviction are rarer than I’d hoped.

- Because deals are so competitive, it also means investors are trying to own as much of these companies as early as possible. If they can’t get the company to come down on valuation because other investors would match the valuation, then they’ll fight hard to get as much allocation as they can. This has resulted in me getting bodied out of several rounds; unfortunately no room for little ol’ Nikhil. I guess I need to hit the investing gym and get my weight up. I’m biased, but I also think founders underestimate their leverage in that situation - if they want to get some value-add angels into the round the venture firm is not going to back off a deal because of a $100K difference.

- The speed at which rounds are getting done is breakneck once a company actually has investor interest. At the pre-seed/seed we’re talking like a month for everything to wrap up, less if it’s a reputable team. My case of COVID lasted longer than these fundraises. It seems like the lead does some modicum of diligence and then everyone else filling out the round is doing proxy diligence based on the lead. There have been several occasions where I’ve talked to a founder, and get back to them in 3 days only for the entire round to have already been finished. I’ve learned to better keep founders updated on my process vs. going dark and re-emerging days later, but it’s always appreciated when founders give me a heads up on their timeline as well.

- Pre-empting a round has become the name of the game. For companies that seem to be doing pretty well, investors are trying to stuff them with more money before they’re even considering going out to raise. This means firms will actually come to startups having essentially pre-diligenced them already if they aren’t investors and ready to move quickly. Existing investors largely have this information, and are trying to find places to back the truck up. It also allows VCs to better control the company’s fundraising process vs. the founder. Instead of having to compete against other firms which allows the company to generate heat, the investor can basically give a “take it or leave it” offer on their terms. This has especially been happening at the later stage:

“Often when we’re speaking to investors, they’d cut me off and say, ‘Let me show you what I already know about you,’” Mr. Perez said. The reverse pitch from Tiger Global, the firm that [Hinge Health] picked to help lead a $300 million funding round alongside the investment firm Coatue Management last January, was 90 pages

A few months after Hinge announced that funding, the reverse pitches started rolling in again. Three different investors sent Mr. Perez videos from celebrities they had hired on Cameo to make their case. One was from Andrei Kirilenko, a former Utah Jazz player whom Mr. Perez was a fan of.” - New York Times

Just FYI, if you ever want to give me money I’d like a Cameo of Vin Diesel saying I’m part of the family. That’s lead investor material.

- One question that seems to come up a lot with founders is how to think about the cadence of fundraising and the amount to raise. This gets particularly tricky in healthcare, because a lot of times you need to raise ahead of a specific time-based inflection point (e.g. open enrollment is coming up, a big contract is going to potentially get signed and you need to staff up, fiscal year discussions are coming so you need a sales & marketing blitz). I don’t think there’s a right answer for this, but I think because fundraising clips have become considerably shorter it’s more of a question of sustaining how hot your company is even between rounds so you can raise quickly as soon as you need to. This generally means that founders seem to always be in “sort of” fundraising mode (maybe this has always been the case, idk), especially if the capital requirements for their business are high.

- I think it’s also possible to OVERHEAT as a startup as well. Companies will raise way more than they thought or make really bold projections or optimize for really high valuations but this can potentially backfire. If you set the bar extremely high or need to grow into a very high valuation, then missing your targets will make follow-on financing a pain in the ass and potentially result in a round with a lower valuation than your previous one which can completely kill company momentum. This is especially important right now with public markets seeing a drop because now there’s valuation compression. You may have been able to raise at 50x revenue before, but if the valuation multiple drops to 12X, you have to have much more revenue to make sure your valuation doesn’t drop in the next round. Another weird dynamic here is that if you’re raising at a similar time as a competitor, raising at a lower multiple can make it seem like you’re a lower quality deal. It’s dumb, I know, just being honest.

- If you’re a founder, just remember that investors keep longitudinal notes about a company so if you make X claim in 2015 and go back to raise in 2017 they’re going to ask about what happened to all those things you said you would make happen. Keep that in mind when crafting your deck and narrative. That prorated expected revenue based on one month of sales is going to come and bite you in the ass.

- The need to keep up the image the company is succeeding for future fundraising rounds does make investor updates interesting. Some companies don’t send updates at all unless they have something particularly good to announce. Other companies put lowlights that are really kind of highlights (“oh my worst quality is that I’m actually TOO ambitious). It does seem to prevent actual conversations about what’s not going well and what can be helped, which sucks because theoretically both parties should be aligned here.

- Because there’s such high demand to get into hot company cap tables from the investor side, founders can sell an increasingly larger amount of their shares in secondary sales much earlier in the company lifecycle (aka selling their personal stock, not going to the company coffers). Personally I think this is kind of weird, though each founder’s personal finance situation is very different. One argument is that it incentivizes founders to take bigger swings + helps de-risk entrepreneurship a bit. This is probably true to a degree as well, but it also means that there’s less reason to try and bootstrap your business without any outside funding if you can make a similar personal financial outcome through secondary sales in a much faster amount of time. It also means it makes sense to optimize FOR fundraising instead of making the economics of the business work, because you can rake in millions on the way up in secondary sales. Venture firms benefit from this because they can say they’re on a company cap table.

- Separate point that’s worth calling out - it sucks that employees generally don’t get the same ability to sell their shares in fundraises. A lot of this is structural - if you let too many people sell, you can trigger a “tender offer” that is more expensive and requires more public data disclosures. Plus, if you let too many employees sell, it can cause your 409a valuation (aka the cost employees buy their shares at) to climb, which is bad for future employees. It would be cool if employees themselves could participate in the company fundraising, but would strongly disadvantage people who didn’t have access to funds.

Everyone’s An Investor

When you start looking at the cap tables of companies you realize that everyone is now an investor.

Scout programs and solo funds have become extremely widespread. Basically every multi-stage venture firm and every growth fund has scouts now, or they’re LPs in <$10M microfunds (which implies the existence of fund-of-fund-of-funds?). Sometimes I’ll look at cap tables and see a friend is also investing, which is how I’ll learn they’re also a scout. Then I tell them I’m a scout, and it feels like a “Hail Hydra” moment.

Angellist Roll-Up Vehicles have become a gamechanger for people who want to write smaller checks. They’re $8K flat to set up and you just send a link to all the people who want to invest - makes the process much much easier. I’ve invested in a couple of these and it’s buttery smooth and makes it more accessible for people who want to invest <$10K, even <$5K.

Syndicates and Special Purpose Vehicles are also ever present, also enabled by Angellist and some other players like Carta. I’ll get hit up from people I haven’t talked to in years asking if I’m investing in X healthcare company through Y syndicate, neither of which I’ve ever even heard of. I’ve barely heard of the person asking me lol.

There are some interesting second order effects of this:

- A deal’s “hotness” can more easily manifest just based on the sheer volume of people talking about the company even if their check sizes are small.

- When thinking about the value a VC provides at the early stages vs. a network of individuals, it gets harder to figure out which is more valuable. Individuals work at potential customers, have more sway over friends who can potentially be recruited, and have operational expertise in a lot of the problem areas a startup might face. Plus, since they usually don’t follow-on finance, a company doesn’t need to worry about signaling risk if an individual doesn’t participate in the next round. Downside is that you have a ton of more passive investors that are generally hands-off, but some people prefer that.

- Usually people’s equity exposure in startups is concentrated in a handful they work at. But angel investing is a much better amount of equity relative to the amount of time spent working, which is kind of weird. It’s not unheard of to have your angel position in a company to be worth more than the 4 years of blood, sweat, tears and confusing reorgs you spent at your startup (for junior and/or later stage employees).

- There’s still an unsolved problem of connecting startups who have a specific kind of angel expertise they want on their cap table to the right person for that problem + isn’t invested in a million companies that all need their attention. There are lots of extremely competent people who have that expertise and would angel invest but don’t market themselves. One thing I’m trying to do is use my shitposting-derived access to companies and better match them to people in my network specifically based on the expertise they have. But actually building that expertise graph on top of your social graph is hard. If anyone has solved this problem, let me know.

- When everyone is an investor, I sometimes wonder if it’s something worth disclosing your investments at the company you work at. If you’re in charge of vendor assessment and you’re an investor in one of the vendors you're looking at, should that be known? In academic fields you have to disclose that conflict of interest; should startups (especially if it’s a choice that affects patient care)?

Team vs. Ideas

When I started investing I made a list of areas in healthcare I was particularly interested in. The idea was that it would make it easier for me to filter through companies quickly if I wasn’t interested in the idea + demonstrate to companies I was excited about that I have very real, publicly stated interest here. What a smart plan, I had outwitted the old guard with such a simple idea.

So anyway, that was wrong. It’s become clear that at the pre-seed and seed stage, ideas don’t really matter that much. It’s basically entirely about teams, largely because there’s a good chance the company's approach or product is going to pivot in the first couple of years. And the reality is that a founder who’s really passionate about an area will get you interested in it too. How they talk about the company idea, their approach, their go-to-market, etc. is a great way to understand how they think through problems and answers should at least represent a good first experiment that you believe in. But it’s not something I need to be wedded to. Teams are really the main thing I’m trying to evaluate, and that I believe they’re tackling a problem that actually exists.

The things I try to understand about teams are:

- The Scientific Process - What is their unique insight on this problem and what is their plan to test that? How does this team think about experimentation to figure out if their model is working or not? Which levers and metrics do they perceive to be absolutely key to monitor/optimize for to be successful?

- Always Be Closing - How good are they at sales and storytelling? (Every founder is a sales person, especially in the early days). How you sell in an investing pitch is a decent proxy for how you sell people to come work for your company and customers to pay you. It also requires an ability to distill complex concepts to the correct level of expertise of the audience, which is a difficult skill. I should be able to write the memo about it after 1 or 2 meetings.

- Founder-Market-Fit - How closely does this team’s strengths match the problem they’re trying to solve? If it’s a marketplace style business, have they demonstrated some ability to solve a cold start problem? If it’s a complicated operations model, are they really detail-oriented or have they run similar styles of teams? Will this problem boil down to sales or product being the key to distribution, and does the founding team have that strength?

- Team Complements - What are the early team dynamics like? Are there clear swim lanes between the co-founders? Who handles which questions during the pitch? Have they worked together before? Do they have similar visions of what the future looks like if things go well? Founder breakups are a huge reason companies die.

- Do they believe they can beat me in a dance off?* - It’s a good assessment of their risk-tolerance and willingness to adjust their beliefs when proven wrong.

{{sub-form}}

These are the things I’d ideally like to learn but I don’t always get to since I usually get like 2 meetings with the team so I just try to do my best. Since I have no data on “success” of teams yet, there are some archetypes of founders that I particularly enjoy working with.

- Flexible experts - These are people that have been working in some part of the industry for years, understand the rules of the game, but realize that the process could be done completely differently today if built from the ground up. In healthcare it’s really easy to get stuck in your ways or not ask “why are we doing it this way?” once you’ve been working in the industry for long enough and get curmudgeonly when someone suggests an innovative approach to the problem in your domain. One of the reasons I like this founder archetype is they tend to be better at hiring for similar people, which is especially important in companies that require a very niche expertise area (e.g. computational biology, revenue cycle management, attracting high quality specialists in a specific disease area, etc.)

- Quick learners - These are people that demonstrate they very quickly know how to get up to speed on some part of the industry and can identify the core ideological questions that experts in the industry still grapple with. I don’t believe you NEED previous healthcare experience to build a great healthcare company - and I think quick learners come from other industries but have systems which let them get to the core problem they believe need solving. This also tends to be an archetype that knows how to set up good experiments to test their hypotheses.

- Deep product people - When someone spends a large chunk of time obsessing over different product interactions they’ve seen that can be improved and thinks in all the interlocking parts from different users, I know that this team is going to be truly customer-centric. Healthcare has a real lack of products end users like using, so if you do believe we’re moving to a consumer-centric healthcare system then these teams will have an edge.

- Regulatory arbitrageurs - Some people just love keeping up to date on the legal changes in their part of the world. “Regulatory arbitrageurs” sounded better than “sad, sad people”. This can be a massive opportunity for companies that benefit from a first-mover advantage. Regulatory regime changes can unlock a ton of opportunity if you build natively to them. Because there are usually no playbooks of success to replicate, founders need to be able to think from first principles how the company would need to be built to be successful.

These are just some of the archetypes that come to mind. I’m sure there will be more I discover as I keep doing this. One open question is whether a person with the above qualities is a better entrepreneur vs. early team employee. Now that more people are realizing the risk-reward of being an early employee kind of sucks and capital is easy to come by, everyone wants to start a company. But seasoned investors tell me that true entrepreneurs are simply “built different”. I’m not totally sure I know what to look for that makes someone a good entrepreneur, and hopefully it’s something I learn over time. I’m curious if you all have thoughts on this.

A Remote World

It’s no secret that the world moving to remote work and remote fundraising has changed the game. I think this has been felt particularly acutely in healthcare because of how many healthcare hubs there are across the US vs. tech which feels much more concentrated on the coasts.

This has clearly been a huge benefit to entrepreneurs. Fundraising processes not only go much faster because you can do back-to-back 30 minute Zooms in a way more efficient way vs. in-person meetings, but also because the number of investors an entrepreneur can talk to increases significantly which means more FOMO for a deal that already has interest. Also, you can do it in sweatpants.

However, one thing I’ve noticed is some entrepreneurs that are just getting started and in non-coastal areas will get really bad guidance from local entrepreneurs in completely different industries/time periods or local finance people. I’ve seen very strange cap tables with egregiously high advisor grants, stacked convertible notes with different caps, or some sort of royalty agreement very early in the company life cycle. I’ve gotten bankers reach out on behalf of companies who for some reason have paid them. I’ve seen decks that are buzzword filled or have insane TAM projections that immediately discredit them in any legitimate investors eyes (your TAM is not $3T, full stop). I’ve even been sent the pitch materials through a non-docsend medium (jokes).

Despite the fact that there’s tons of information out there right now about the do’s and don’ts of raising as a tech startup, the reality is that people trust the advice of other people they view as successful. When you’ve been in tech long enough, it’s easy to take for granted that you’re surrounded by people every day you respect who are in a very similar industry/position as you and can give you advice. If you don’t have that, it’s easy to default to the people in your sphere you think are successful but have 0 experience doing what you’re doing.

This is where I think really early stage investors can play a huge role. Helping navigate a lot of the inside baseball for new entrepreneurs with less connections in the startup world can be immensely helpful, especially when it comes to figuring out fundraising dynamics and norms. Even for experienced founders, having advisors and investors they deeply trust that they can regularly soundboard with during a fundraise process is hugely helpful. Several founders I’ve spoken with praise YC for this exact thing + use their influence to back founders up when they see bad practices. I don’t quite have the $100Bs of exits under my belt, but I try to be helpful with navigating fundraising when possible even if I haven’t invested in a company. It’s just good form.

Miscellaneous Thoughts

Some other random observations that don’t really fit into any of the buckets above.

- I’ve been surprised at how often disagreements about the size of the market come up with other investors. I’m generally in the camp that great products will unlock larger markets or entrepreneurs will figure out other areas that a product will be useful that we can’t see today, and therefore worrying about market size at the early stage is largely a fruitless exercise. However, it’s worth thinking about how defensible and large the “first act” of the business is to enable the company to explore these other areas.

- I usually send the investment memos I write about the companies back to them - I find it helps to make sure we’re both on the same page in terms of where we think the strengths and weaknesses of the company and team are.

- I think angel investing in other companies is actually pretty helpful to just see how other companies operate at a very high level, the problems they go through, etc., which actually will likely help you in your own job as well. If you’re able, I recommend angel investing a little bit just to get some exposure to the thought process of a few other companies as they grow (and if you ever consider a new job, you’ll have a more longitudinal relationship with those companies to know if it’s a good fit for you). Personally, it’s been fantastic to see the common pain points founders face which helps when I’m writing analyses + the infectious optimistic energy of early stage founders keeps me from getting too jaded :)

- Raising notes with no valuation caps is weird! It feels like it messes up the founder-investor dynamic because investors actually then want companies to raise the next round at the lowest possible valuation instead of growing as much as possible between their round and the follow-on financing. Pushback I’ve heard here is that it’s for companies that need to optimize for speed of fundraising and useful when a company needs a bit more extra cash for a short period of time to get to an inflection point before a more formal and larger fundraise. The uncapped note also helps avoid signaling risk based on a valuation change that would occur if you were to price the round.

- Another open question entrepreneurs have is whether corporate venture investors and strategics are good to raise from. The general vibe I seem to get from people is that a lot of these funds don’t actually have enough internal sway at their respective companies to help a startup actually get deployed. So the key is finding the funds with case studies/examples of companies they actually have had success bringing in or have an established process they use to do this. Chris Leiter wrote an excellent thread on the different types of corporate VCs, how their investing committee actually works, etc. for people thinking through this.

- A similar version of this is looking for venture firms who have LPs that would be potential customers. Is going through the venture firm better than having an angel that actually works at the company you’re trying to sell to? It depends on the LP<>VC relationship.

- Every founder deciding between venture firms should backchannel the firm, not only through other successful founders they’ve invested in but more importantly for companies they invested in that did not make it. This will give a better indicator of what the firm is like when you actually do need help.

- Tech is a small world, digital health is even smaller. Reputation matters a lot, so if you’re debating between decisions that trade reputation for short-term benefits, choose reputation and integrity IMO. My hope is that over the long-run it’ll be best for all parties involved.

—

That’s all for now! I’m learning too, and hopefully these observations are useful for entrepreneurs entering the fundraising process or new angels in healthcare. Looking forward to all the old heads to call me out on my naivete.

All I care about is that I’ve upgraded from “brilliant advisors, also Nikhil is involved” in press releases (shoutout to Axle Health and Neura Health for letting me invest though).

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “more like as SWELL as 🥲”

Twitter: @nikillinit

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

Lol all four people that gave comments on this want to be anonymous, uh oh. Thanks though!

*hopefully it’s clear this is a joke, but also hopefully it’s more clear that you will lose

{{sub-form}}

---

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.