Match Day and the Unmatched

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveIntro to Revenue Cycle Management: Fundamentals for Digital Health

Network Effects: Interoperability 101

.gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

Have you ever thought “damn I wonder what would happen if we took the same exact process as college greek life and applied it to grown ass adults with career-altering consequences?” Fear not, we have Match Day.

Match Day is when med students find out about the residency programs they will be going to. As a third-party observer, there’s a nice flood of people joyously reacting to getting their top spot after years of working hard. Even my cold, dead heart beats a little watching these videos.

You could legit write an entire book on this topic, so I thought I’d collect a few interesting things I learned reading up on Match Day.

I really want to thank Bryan Carmody for his absolutely excellent blog where he discusses a lot of the nuances in medical education and how to change it. It’s called the Sheriff of Sodium because he’s “salty about medical education” lmao which should sell itself. I learned a lot just from going through it, especially his short, informative series on the history of Match Day.

Applying and interviewing

In the last year of med school, students will submit an application into the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS). This will include a personal statement, letters of recommendation, MySpace top 8, “Dean’s Letter”, transcript, a photograph, and licensing exam transcript. International medical graduates have to include a few other things.

Then you choose the programs you want to apply (specialties + schools). You fly around interviewing at these different schools, telling residency program directors and faculty how you’ve been passionate about medicine ever since [childhood story about you/family member’s health experience, previous work at healthcare setting, trip that opened eyes to health inequities].

Students rank the programs, programs rank the students, and an algorithm spits out where everyone is going next year. Students found out whether or not they matched anywhere last Monday. On Friday, they receive an envelope because healthcare thinks communicating critical information through paper is still fine, and inside is which program they’ll be going to. If they don’t match, there’s a separate process which I’ll talk about a bit later.

What I wanted to look at is the general cost of going through that process. Here is the pricing structure for applications which, according to unofficial healthcare laws, has to be confusing and based on weird logic.

- Ten or fewer: $99

- 11-20: $16 each

- 21-30 $20 each

- 31 or more: $26 each

The average numbers of programs someone applies to was 36.4 in 2015. Most people seem to interview ~12 schools so you need to add flight, lodging, food, etc for each.

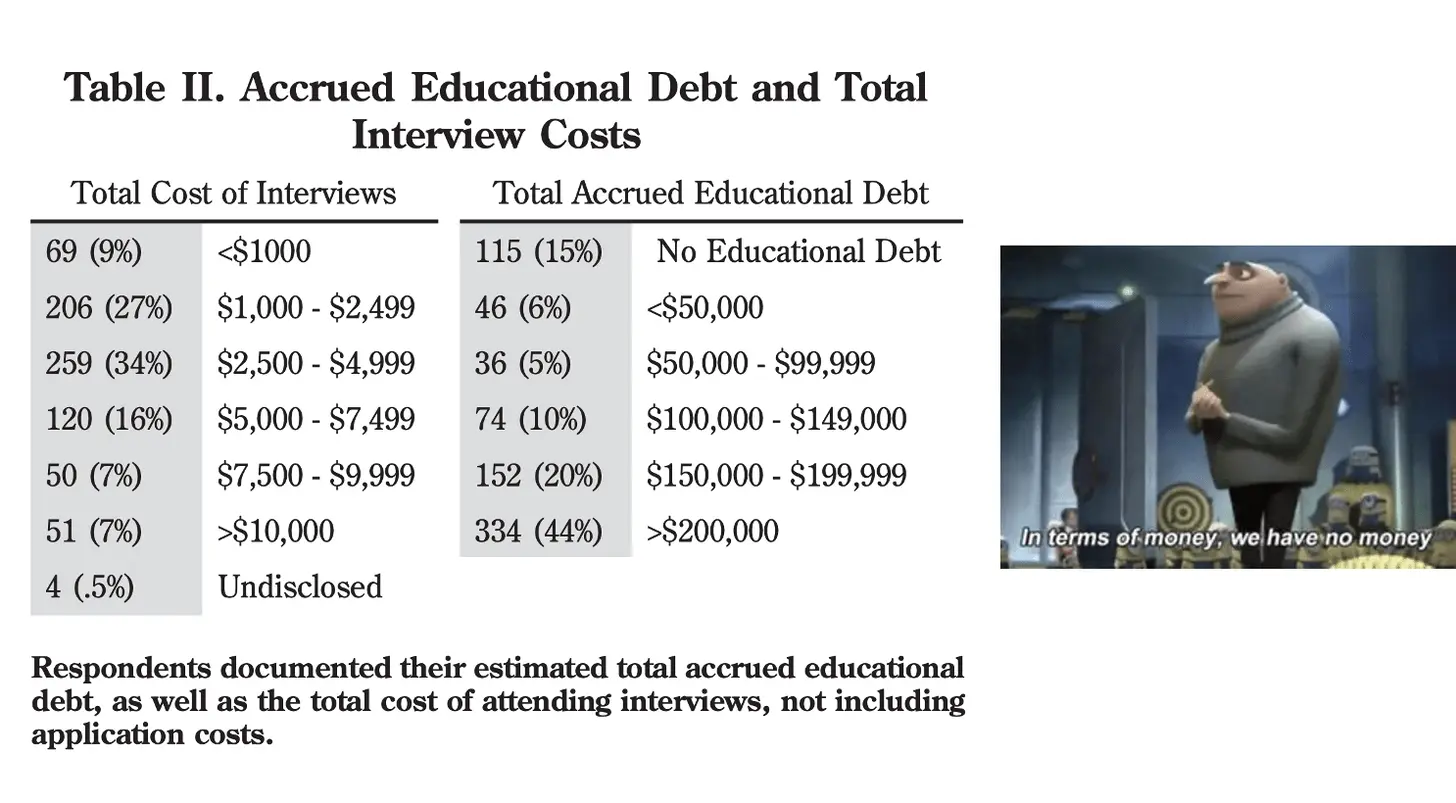

Looking at this study, about 14% spent more than $7500 just to APPLY for residency. 44% of those people had more than $200K in loans. 71% of people in the study borrowed money to fund interviews and 41% declined interviews due to financial reasons.

COVID has posed a twist to this scenario. Because everything is done over video, theoretically you can actually interview at way more places since travel and cost aren’t a restriction. It’s possible that without a physical visit students might not have as much info about the program, school setting, etc. and potentially misrank their programs. However, since an entire class year had to do this, we should be able to assess satisfaction scores later and see if virtual interviews actually decreased satisfaction with their program choices across the board. My guess is most people end up happy wherever they go regardless of the interview process, or at least the sunk-cost fallacy kicks in and convinces them it was a good choice.

A separate question is whether more interviews actually helps everyone. This paper surveyed ~2500 people this year applying to OB/GYN programs to see how many interviews they received and completed. They then modeled out 4 scenarios using that data: whether or not the programs increased the numbers of interviews they did by 20%, and whether or not the applicants were capped at only applying to 12 places or not.

They found that, using the survey data, the interviews would actually concentrate in a handful of applicants if not capped. This would theoretically be bad for everyone since programs would likely have more unfilled slots since they’d be competing for the same people, and less applicants would get offers. Hence they suggest potentially capping the number of applications.

The Rankings and Algorithm

The actual matching process between students and residency programs is governed by a complex algorithm. The match algorithm has evolved significantly over time, and I recommend reading this if you want to see how.

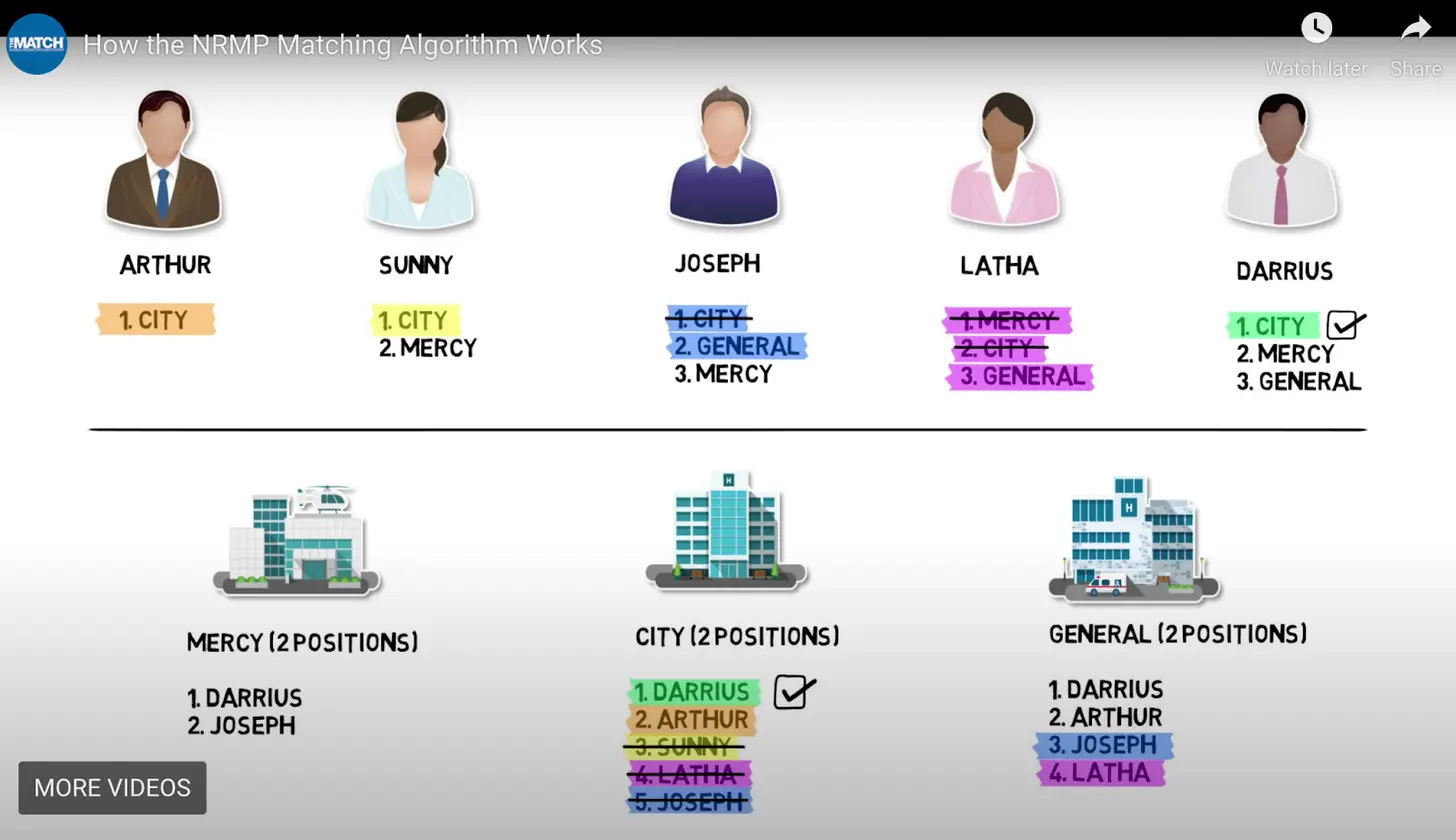

The final version of the algorithm which is used today actually won the Nobel Prize. The initial version of this was called the “Gale-Shapely” algorithm, which deduced that you could actually find the most optimal match for marriage if everyone could rank alternates and the final decision for everyone was made at the same time. It turns out that there’s a lot of similarity between picking marriage partners and picking residency programs in that I’m involved in neither.

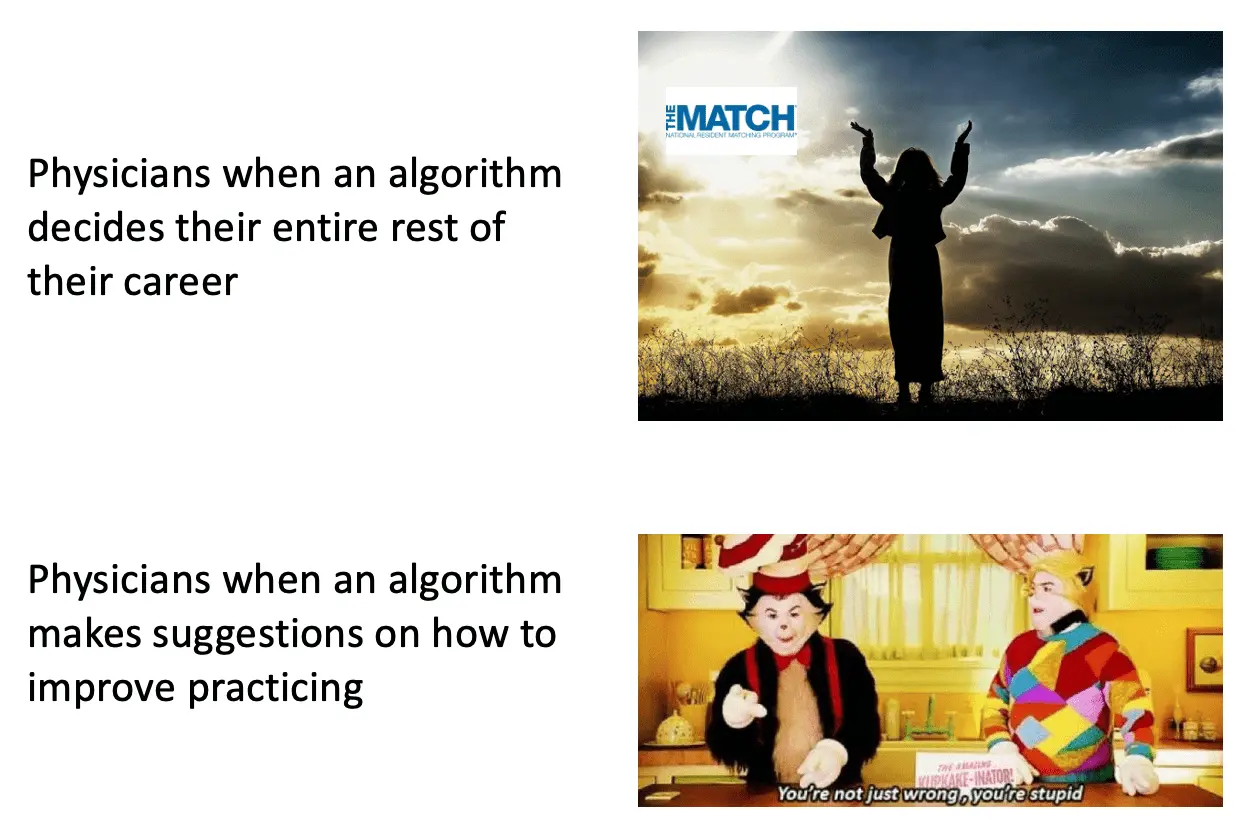

It’s pretty cool to see how the algorithm actually approaches matching. You can see a walkthrough in this youtube video, which unsurprisingly has disabled comments lol. The general gist is that both programs and residents rank each other in order, and then the slots are selected on the highest possible match pairing (e.g. if a program and resident match each other as #1, that’s essentially locked in since there’s no better pairing). Importantly, the algorithm is “student proposing”, meaning it favors the students ranking for optimal choice instead of the hospitals (there’s a whole backstory to this.)

This makes sense if all the rankings are done blindly, but several people reached out to me after I said I was writing this to tell me about how rampant informal behind-closed-doors dealings were. Program directors “suggesting” to applicants that they’ll rank them #1 and the student should do the same. This is especially bad if programs tell applicants this and then actually NOT go through with it. The applicant gets screwed and then has no real recourse because it’s technically not allowed. Even though the algorithm favors students, the process still demonstrates how tilted the power dynamics are in hospital-resident relationships.

Residency matching is one of the few real-world places the Gale-Shapely algorithm was deployed because it needs certain criteria:

- It requires coordination from competitive parties

- Everyone has to go through a recruiting process at the same exact time

- It requires releasing the results of the match at the same time.

Residency is one of the few places all of this seems to line up...or are there others? Recruiting season in college seems like an akin and obvious place. But what about accelerators? Could startups lining up for demo day and investors looking to pitch startups actually benefit from the application of the Gale-Shapely algorithm to find the optimal match?

The Unmatched

On Monday, some students unfortunately received an email that they did not match to any program. At this point, students would “scramble” and start ad-hoc calling and looking for programs with unfilled spots. In 2012 this was turned into a more formalized process called Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program (SOAP) so that the organizing parties could say cutesy stuff like this to people who just had a bomb dropped on them.

SOAP is bogglingly intense. You find out you didn’t match to a program, and basically within an hour you have to look up which programs aren’t filled, quickly get all of your documents/letters of recommendation, and apply to those programs. Then you do interviews within 24 hours and basically say yes to whatever you can get which can be totally different specialties, geographies, etc. This essentially happens within a 2-3 day period after finding out you didn’t match, which is still just insane to me. If you don’t find anything through SOAP, then there’s an actual scramble where you just call around and see if there’s anything left.

SOAP seems to be getting much more popular in the last couple of years.

The reality is that a lot of folks will still go unmatched. Across all applicants, US or international med graduates, the number of unmatched actually seems to be steadily decreasing over time even combining the unmatched and no rank lists. This is not what I expected. It’s possible that more people are potentially dropping out before even getting to the match part of the process as well.

But there are still 10K+ people that completed med school that didn’t end up with a residency but still likely have enormous sums of debt. I couldn’t find data on how many of these folks left medicine altogether, but it’s hard not to read these stories of people going to med school, graduating with $440K in loans, and then not matching and working in dishwashing/parking attendant jobs instead. It feels like even if not practicing doctors, there should be more available roles for them in support functions with the level of knowledge they have.

An interesting experiment is happening in Missouri and Arkansas which has created a new position called Assistant Physician for these unmatched graduates. This is an entirely different role from a Physician Assistant. Please don’t ask me any further questions about the naming choice or I will get more upset than I already am after learning these are different.

Assistant Physicians were created to help with the primary care gap in rural areas. An unmatched student signs a collaborative practice agreement with a primary care physician. They train in their practice for 30 days, and then can practice within 50 miles of the original physician (and 10% of their charts get reviewed periodically as an audit).

I like the experiment, but don’t understand the geographic piece. Why can’t a physician anywhere do the chart review and be available to ask questions? In fact you can probably link the Assistant Physician data to a registry and immediately see if their practice patterns fall outside of the norm. There are stigma, operational barriers, and very valid concerns about risk incurred to the supervising physicians if something goes wrong. Only 25% of the initial Assistant Physicians in Missouri could get a collaborative practice agreement signed.

Existing primary care docs clearly do not like this model, and are already putting out these studies analysing the Assistant Physician Step 1 test scores. What should matter is whether patient outcomes were equivalent and whether patients who may have never seen ANY physician were able to get care (with improved outcomes vs. no care at all). 80% of those Assistant Physicians were practicing in shortage areas. We’re still relying on test scores and brand names as proxies instead of actual outcomes, which feels so 2008/2000-and-late.

That being said, I understand the concerns of potentially having less than qualified docs seeing patients. But if we know for a fact that patients not seeing doctors at all due to access issues is deteriorating their health outcomes, isn’t it unethical NOT to try and find ways to increase their access to care?

As we get outcomes and performance data, I think this is a program worth expanding or potentially adjusting. Maybe there’s a longer ramp up period where the scope of practice increases over time as the Assistant Physicians demonstrate competency, or the scope is focused on triaging/disease management instead of diagnostics.

It’s just hard for me to believe that the best place for people with 4 years of medical training is outside of healthcare completely. I think this is especially true when you consider that virtually no graduating residents want to work in small towns which tend to have shortages. However, a (marginally) larger % of international medical graduates do, and they tend to be where most unmatched students are (which I’ll talk about in the next section).

I think it’s worth seeing where unmatched residents can play a role here.

International Medical Graduates (IMGs)

It’s impossible to talk about match day without talking about International Medical Graduates (IMGs). This is pretty specifically talking about for-profit medical schools in the Caribbean.

For some context, in the 1970s a few wealthy enterprising folks responded to the shortage in US medical schools (and non-shortage of US taxes) by setting up their own med schools in the Caribbean. The big ones are:

- St. George's University School of Medicine. (The original one)

- American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine.

- Saba University School of Medicine.

- Ross University School of Medicine.

You can actually see how much residency match rates change starting around then. Before that there were more positions than applicants!

Generally speaking it seems like depending on how you count “unmatched”, IMGs only match 50-60% of graduating classes vs 93%+ match rates for US med school graduates. Actually non-US citizen IMGs have been steadily improving their match rates over time while US citizen IMGs are one of the only groups across the board whose match rates have slowly gotten worse.

These schools are easier to get into than their US counterparts, and have a reputation amongst US docs as being less rigorous and producing worse physicians. Just take a look at this lovely and supportive comment on a New York Times article about the schools.

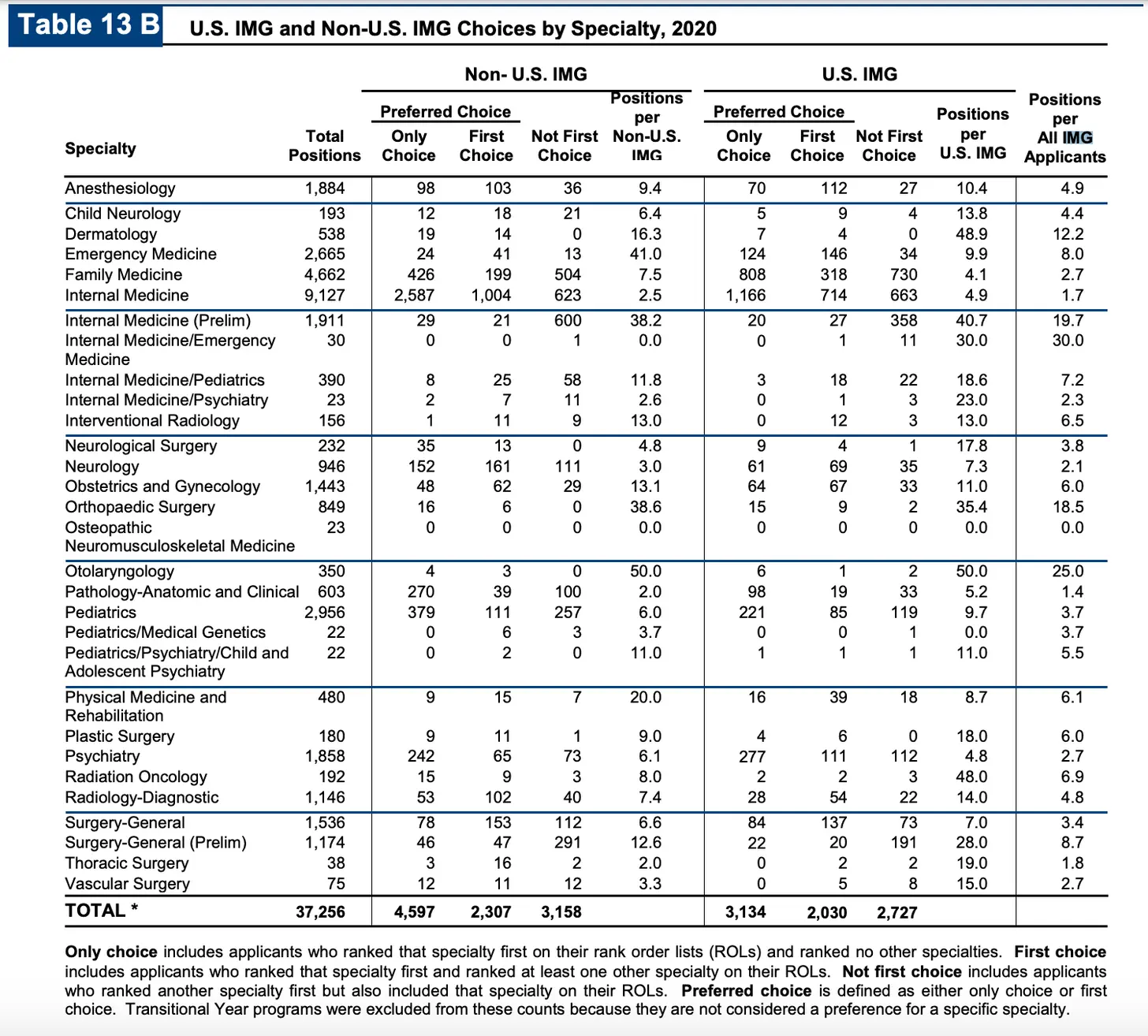

So are these schools actually worse in terms of quality of education or graduate they produce? Frankly it’s hard to tell, but I think most people will tell you that there’s a lot of quality variance between the schools and amongst students within the schools. Many IMG graduates get residencies in extremely competitive fields (e.g. surgery specialties).

As with anything there’s a wide variance - and have heard anecdotally that programs will use IMG program status as a means of quickly screening out candidates of interviews since they don’t have the resources to go through so many applications. This is becoming especially challenging as Step 1 tests have moved to pass/fail, so any students trying to shine at Caribbean schools with stellar Step 1 scores can no longer do that.

So far I could only find data on Step 1 pass/fail rates, but haven’t seen any papers that longitudinally track IMGs vs. any type of quality scoring metrics. Again, sort of feels to me like we need individual physician level accountability/scoring vs. defaulting to the quality of the institutions they’re a part of. If anyone has actual data showing how graduates of these programs compare to US grads I’d be curious.

Parting Thoughts

Residency slots are largely funded by Medicare and Medicaid. There is some interesting nuance to how this actually happens which I’ll do some research on and talk about another time. But the main thing to note is that since 1996 there has been a cap on the number of residencies it will pay for.

When I told people I was writing this, a very common reaction was “it’s crazy because we have a physician shortage but so many people can’t become physicians because of this cap!”

I’m not sure if this is definitely true. Questions for further research:

- If we first expanded scope of practice for non-MDs and removed the telemedicine barriers (e.g. state-by-state licensing), would that first solve the shortage with existing supply, for less money, and with equal outcomes?

- What do the outcomes look like for people that do not match (e.g. the people who would get the additional residency spots)? You can look at the outcomes of assistant physicians as a proxy here probably. Would increasing the spots lower the median resident quality?

- Is residency lucrative enough for hospitals in the form of relatively low-paid labor relative to what they bill for? Could hospitals add more slots without needing a funding boost from Medicare? This article lays the case out that it might be possible without more funding at all. I don’t know enough about this to agree or deny.

Idkkkk I think this is more complicated than the black and white issue people think.

Either way, I’m really happy for all my newly matched resident friends. You’ve all worked hard and deserve to celebrate! And if I know you personally you’re giving me free consults for the rest of my life so remember my “congrats!” text k byeeeee.

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. “everyday is unmatched day”

Twitter: @nikillinit

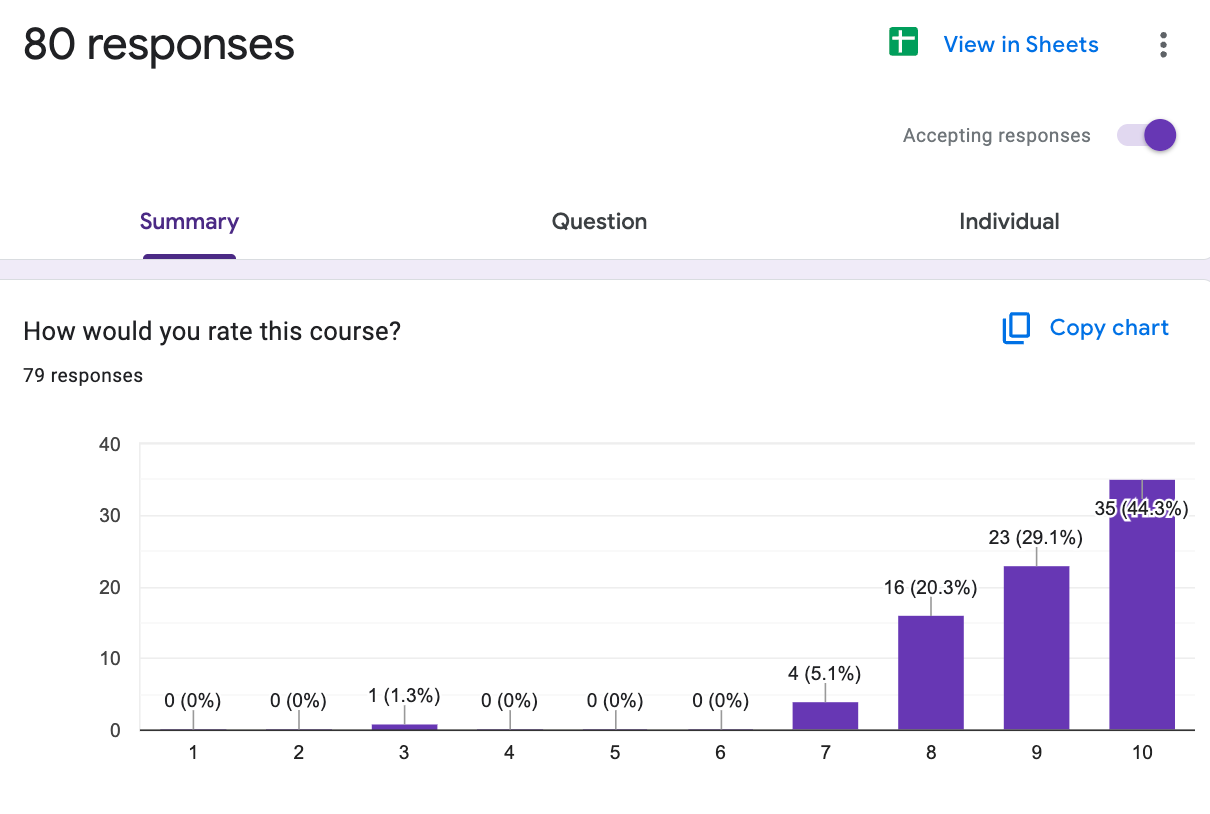

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!!

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →A reminder that there’s a few courses STARTING VERY SOON!! And it’s the final run for all of them (except healthcare 101).

LLMs in healthcare (starts 9/8) - We break down the basics of Large Language Models like chatGPT, talk about what they can and can’t do in healthcare, and go through some real-world examples + prototyping exercises.

Healthcare 101 (starts 9/22) - I’ll teach you and your team how healthcare works. How everyone makes money, the big laws to know, trends affecting payers/pharma/etc.

How to contract with Payers (starts 9/22) - We’ll teach you how to get in-network with payers, how to negotiate your rates, figure out your market, etc.

Selling to Health Systems (starts 10/6) - Hopefully this post explained the perils of selling point solutions to hospitals. We’ll teach you how to sell to hospitals the right way.

EHR Data 101 (starts 10/14) - Hands on, practical introduction to working with data from electronic health record (EHR) systems, analyzing it, speaking caringly to it, etc.

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

INTERLUDE - FEW COURSES STARTING VERY SOON!!

See All Courses →Our Healthcare 101 Learning Summit is in NY 1/29 - 1/30. If you or your team needs to get up to speed on healthcare quickly, you should come to this. We'll teach you everything you need to know about the different players in healthcare, how they make money, rules they need to abide by, etc.

Sign up closes on 1/21!!!

We’ll do group rates, custom workshops, etc. - email sales@outofpocket.health and we’ll send you details.

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.