Why don’t we screen healthy people to catch diseases early?

Get Out-Of-Pocket in your email

Looking to hire the best talent in healthcare? Check out the OOP Talent Collective - where vetted candidates are looking for their next gig. Learn more here or check it out yourself.

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collective

Hire from the Out-Of-Pocket talent collectiveHealthcare 101 Crash Course

%2520(1).gif)

Featured Jobs

Finance Associate - Spark Advisors

- Spark Advisors helps seniors enroll in Medicare and understand their benefits by monitoring coverage, figuring out the right benefits, and deal with insurance issues. They're hiring a finance associate.

- firsthand is building technology and services to dramatically change the lives of those with serious mental illness who have fallen through the gaps in the safety net. They are hiring a data engineer to build first of its kind infrastructure to empower their peer-led care team.

- J2 Health brings together best in class data and purpose built software to enable healthcare organizations to optimize provider network performance. They're hiring a data scientist.

Looking for a job in health tech? Check out the other awesome healthcare jobs on the job board + give your preferences to get alerted to new postings.

"Let's do more scans"

This tweet was going around recently.

As someone who sits at the intersection of healthcare and people that have read Zero to One, a frequent question I get is, “If a test can help us detect diseases, why don’t we do it more often to catch things earlier?”. I understand the logic - if we screened people more often, we’d find things earlier, and we’d prevent them. The more data, the better. If we scaled down the cost of MRIs, this could be available to everyone.

But it’s not exactly a cost thing. Doing more tests can actually cause more harm than they help. As per usual, Twitter is a terrible place to have that discourse because everyone is really condescending and aims to get the dunk. Hopefully we can have a more interesting and nuanced discussion here.

What happens when we screen lots of healthy people?

Let’s lay a bit of groundwork before getting into this. I basically failed statistics in college - so I’m either the worst person to explain this or the best person because I communicate in single brain cell-speak.

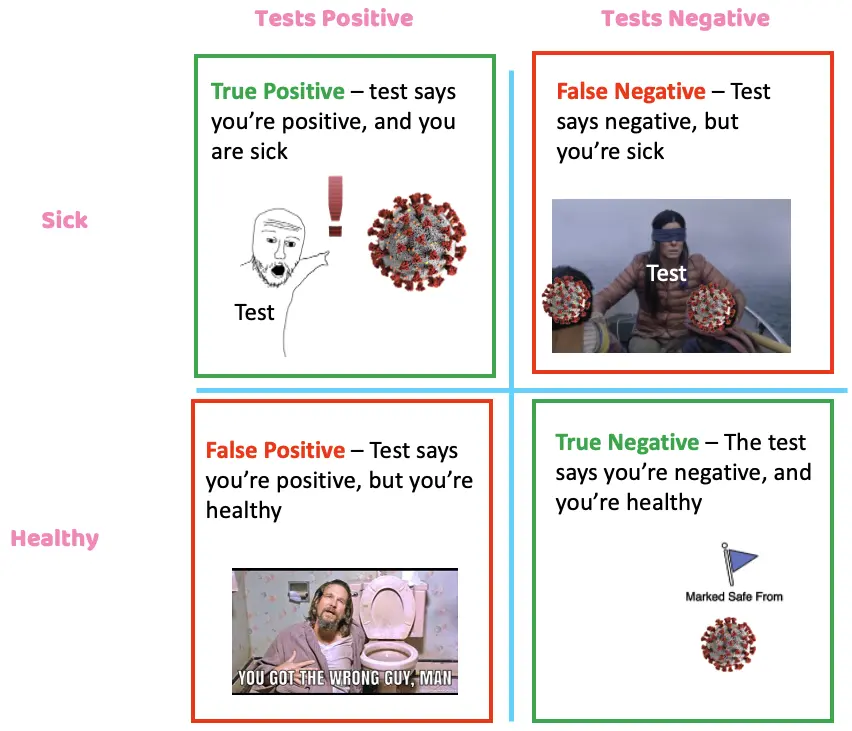

First, let’s refresh ourselves on sensitivity and specificity. These tell us how good a test that‘s trying to find a disease is.

Sensitivity - the probability that if you have a disease, the test will detect it.

- If you’re sick and it tests positive, this is a True Positive. We want this.

- If you’re sick and it tests negative, this is a False Negative. We don’t want this

Specificity - the probability that if you DON’T have the disease, the test will say you don’t have the disease.

- If you’re healthy and it tests negative, this is a True Negative. We want this.

- If you’re healthy and it tests positive, this is a False Positive. We don’t want this.

Ideal tests are great at both. Unfortunately, the reality is that most tests make a tradeoff between the two, and the point of research and clinical trials is to figure out what the tradeoff is. Sensitivity/specificity is the basic foundation for understanding the risk, cost, disease prevalence, and patient experience when it comes to a given disease, biopsy, and treatment. Balancing all of these is not super straightforward.

Let’s give an extreme, theoretical example. The prevalence of Nikhilitis in the population is 1:1,000. It causes incontinence, erectile dysfunction, generally bad vibes, and a 1% chance of death.

We’ve developed a test (a stool sample) with a sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 90% in detecting Nikhilitis. A real estate investor on Twitter that loves making random Twitter threads goes viral about how everyone NEEDS to get this test and how NO ONE is talking about it. So about 1,000,000 healthy people show up to get screened with this test. What happens?

Out of the 1M, we know that 1,000 of those people have the disease in this group.

- Prevalence (1:1,000) * Number of people that came in (1,000,000) = 1,000 people that have Nikhilitis

If we test all 1M, the test will correctly catch 990 of them and miss 10 of them thanks to the sensitivity.

- Sensitivity (99%) * Number of people that have it (1,000) = 990 caught

However, where it really gets dicey is false positives. Remember, 999K people came in that DO NOT have Nikhilitis and the test has a 90% specificity, which yields 10% false positives.

- Specificity (90% aka. 10% false positives) * Number of people that came in who DON’T have Nikhilitis (999,000) = 99,900 false positives

Thanks to a 90% specificity, 99,900 people in that group will get a false positive test. So we correctly identified 990 people that had Nikhilitis, at the expense of 99,900 false positives.

Now we need to follow up with everyone that got a positive test result and do a biopsy. Let’s say a confirmatory diagnosis for Nikhilitis is a lobotomy with a .1% mortality rate. If Nikhilitis only causes 1% chance of death, was this worthwhile to do on everyone?

- 99,900 false positives + 990 correctly positive = 100,890 that need biopsies

- 100,890 need biopsies * 0.1% mortality rate of biopsy = 100.89 deaths from biopsy

Vs.

- 990 correctly positive * 1% chance of death from Nikhilitis = 9.9 people saved

Doing the confirmation would kill 99.9 in that false positive group + 0.99 in the correctly positive group. And would save 9.9 people that we could confirm the diagnosis in the correctly positive group.

So in the end, we killed 101 people to save 10 people. This is an extreme example to illustrate the point, but you can see how large these false positive numbers get (even with a pretty goodtest!) if you just haphazardly screen the entire population. Now imagine we start layering things like cost, % chance the treatment actually works, etc. and it starts getting very complicated quickly. That’s why there are guidelines in place for who should be screened - you want to limit it to a population that has a higher likelihood of having the disease.

The four main problems when healthy people are screened

Here are the main issues that happen when you implement unnecessary screening in the real world.

Lots of follow up tests - If something irregular is found during a screen, a whole host of downstream things will need to happen to confirm or throw out a possible diagnosis. These are called treatment cascades. There’s a good paper here with an insane McDonald’s PlayPlace looking graph that shows how these cascades can catch things clinically important (64.6%), but in a vast majority of cases, they cause some harm financially, psychologically, or physiologically (83.1%). It doesn’t go into whether catching those things improved the patient’s life, either.

Physical harm during biopsies - I really can’t stress this enough - many biopsies are invasive and can really harm you or mess up your quality of life. I mean, it's a bigass needle that needs to find its way into a precise spot to grab some cells or a tube going down an orifice in the not fun way.

Here’s a study that found about 10% of lung cancer biopsies caused a pneumothorax. Liver biopsies cause a fatal hemorrhage in 4/10,000 cases. Sometimes stories get the point across more than stats - here’s a poor woman with an underlying condition, whose neck was broken in half trying to get a regular lymph node biopsy. This isn’t to scare you, but I think when you’re young and healthy you don’t think as much about the biopsy and downstream stuff. Those small percentages start adding up if everyone were to suddenly get these tests.

You would’ve been fine anyway - If you look hard enough and long enough, you’ll find something wrong with everyone. Sometimes scanning for things will accidentally find other issues like benign tumors called incidentalomas because doctors have a sick sense of humor and are also bad at naming things. The question is whether or not that issue will harm you.

This is a difficult point to communicate: even if you have a disease, you might be fine without treating it anyway. For example, you might have cancer, but it could be slow growing and not causing any symptoms to the point where it didn’t even take any years off your life. Detecting that you have cancer is just one part of the story; if it’s not something worth treating, then what did we actually do? Some people might end up going down relatively toxic treatment paths for no real reason, but also don’t want to be told they shouldn’t do anything.

Wasting time, money, and resources - With all the talk about how docs are overworked and the healthcare system spends too much, reducing the number of “low value tests” that create a lot of unnecessary downstream work and cost seems like a great place to target. Here’s a paper that looks at EKGs that happen before cataract surgery for Medicare patients. In this one slice alone, they conclude that ~$35-38M is incurred due to increased downstream tests. And this is despite the fact that most studies and medical societies agree they’re pretty low value. It’s one of those things that sound great at a macro level, but if you’re the one in the chair and someone says you should get an EKG “just in case”, you don’t want to be that one case they could have avoided. Especially if a payer is covering the bill.

Cancer screening gone wrong - Prostate and Thyroid

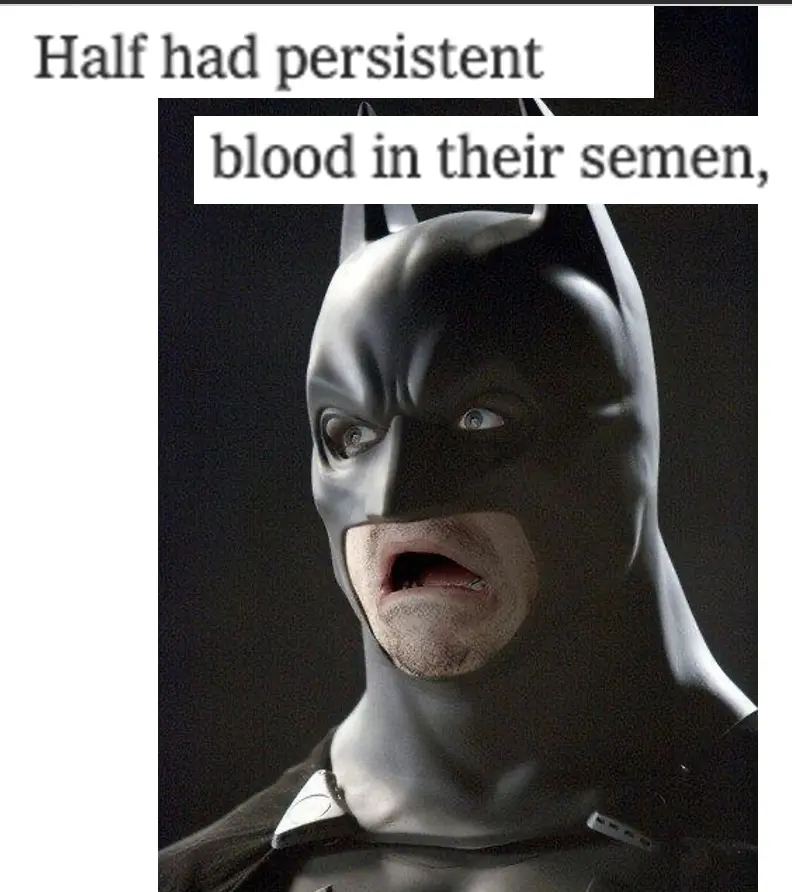

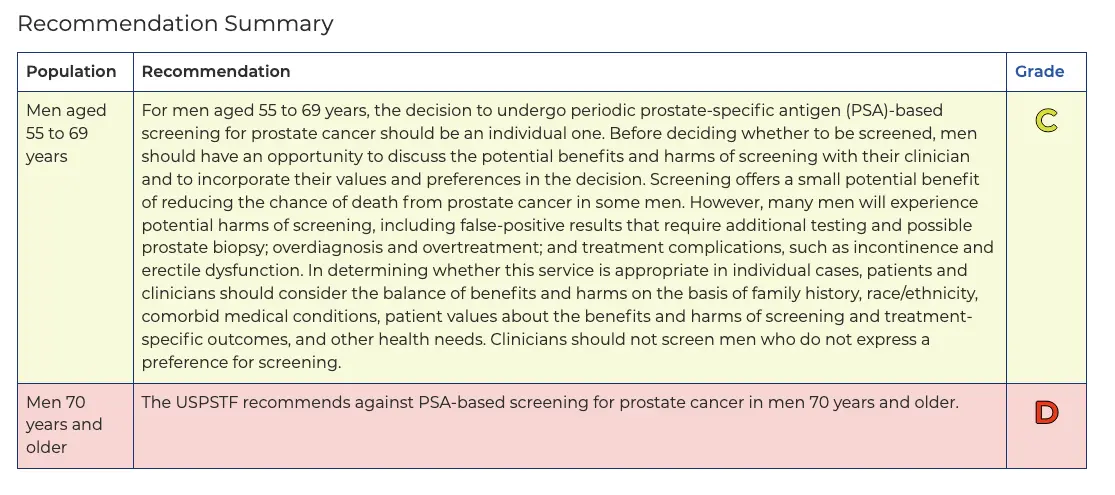

In the late 1980s, the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test was approved by the FDA, and in the early 1990s, it was recommended for men above age 50. However, starting in 2008, a few large studies started coming out with different information. Some studies suggested the screening test was actively harming people due to biopsy and treatment complications.

Part of the reason was the fact that prostate cancer is largely a very slow growing cancer, and most people actually end up dying with it instead of from it. It can become aggressive, but the PSA test couldn’t really tell if it was a slow or fast cancer. How exactly do you communicate that to patients? “Yeah you have cancer, but honestly it’s probably fine don’t stress haha that’ll be $15,000”.

A look into the biopsy and treatment for people screened for colon cancer was not painting a pretty picture either:

“As the PSA test has grown in popularity, the devastating consequences of the biopsies and treatments that often flow from the test have become increasingly apparent. From 1986 through 2005, one million men received surgery, radiation therapy or both who would not have been treated without a PSA test, according to the task force. Among them, at least 5,000 died soon after surgery and 10,000 to 70,000 suffered serious complications. Half had persistent blood in their semen, and 200,000 to 300,000 suffered impotence, incontinence or both. As a result of these complications, Richard J. Ablin, who in 1970 discovered a prostate-specific antigen, has called its widespread use a ‘public health disaster’. ” - New York Times

A heated debate ensued - pharma companies, advocacy groups, some doctors, etc. all disagreed with the task force. Later, one of the large scale studies in Europe would suggest that the test did reduce mortality a bit, so it was conflicting. Though the task force initially said the screen harmed more than it helped in 2012, they changed it in 2018 to recommend the test for very specific subgroups that were at higher risk (e.g. African American men + people with a history of prostate cancer) in light of new data.

There are lots of other examples of this. In Korea, they started doing widespread screening for cancer and other diseases in 1999. Thyroid cancer incidence in particular skyrocketed, so if you looked at the chart you would think that cancer rates in Korea were increasing like crazy. However, mortality rates due to thyroid cancer basically were unchanged, which suggested that increasing the screening wasn’t changing anything. Instead, people were subject to a battery of tests and treatment for no reason.

These are examples of how rolling out cancer screens may not always be a net positive and it’s unrelated to cost. A lot of these guidelines also end up changing thanks to new data that comes out over the longer term about whether we’re impacting the thing that actually matters: mortality.

Current issues with rolling out screening

The value of a life - The uncomfortable truth that no one wants to say explicitly when designing these screening guidelines is, “We’re comfortable with missing ____ cases of a disease that might cause ____% death. This is to prevent _____ people from getting unnecessary tests/procedures, which in itself would cause ______ deaths and other costs.” But you’re asking people to agree to this when it might miss THEIR case. I don’t think people are very thrilled with the current state of societal agreements to begin with, and they don’t exactly see any benefits of skipping testing. Maybe we should pay some people to NOT get screened haha…that’s a bad idea, right…?

Trust - I think the reality is that patients build trust in doctors when it feels like they’re “doing” something and listening to them. The reality is that “testing for stuff” is a big part of doing something. I would guess that doing more tests increases trust from patients that their doctor is taking them seriously, and this is compounded by all of the incentives doctors have to order the tests (fee for service, malpractice, etc.).

The consumption trend in healthcare + science communications - This also strikes at why science communications is so difficult. We need to engage at-risk people that do need to be screened and aren't getting their tests done. But we also don't want to spread a message too wide that people not at-risk also get screened. It’s hard to add nuance to screening campaigns, which adds to the confusion if you’re a patient being told that this disease is an issue.

Also think about how hard it is to walk back a screening campaign if you discover later that actually the risks of broad screening outweigh the benefits. It’s so much easier/more palatable to tell people, “Hey you should get screened to check if you have X disease.” than to say, “Screening can be bad for you, make sure you’re a good fit.”. This is compounded by the fact that every entity in healthcare wants you to consume more healthcare services, an issue I’ve talked about at length.

The difficulty in evaluating if a screen is working - Like most tests in healthcare, we tend to start rolling things out when we have a general semblance of its benefit. But it can take decades to see if it moved the needle on health outcomes and mortality. How do you evaluate whether the screening is working? And when do you start telling people to get screened?

As an example - there was recently a study looking at the benefits of colonoscopies. It was randomized, large, over 10 years, etc. which is pretty much as good as you can get from a study. However, it demonstrated that these screenings didn’t REALLY reduce the risk of death from colon cancer by too much, which then calls into question whether the screening is actually worthwhile. But a ton of well-written editorials argued that too few people in the study actually came in to get a colonoscopy after getting invited (only 42%), the person performing the colonoscopy matters a lot, treatment pathways in the tested countries are very different from the US, etc.

My point is that it’s…really hard to even figure out if screening is worth doing and that may change a lot as new data comes out. How do you figure out the best way to evaluate screening and how do you communicate that to physicians/patients? Think about how many ads you’ve seen telling men to go get a colonoscopy - imagine what would happen if we had to walk that back. I literally got this email 2 days ago.

I don’t think the follow up email is going to work nearly as well if they roll it back. You can’t forget an unnecessary colonoscopy.

The impact of lawsuit culture - The US is a pretty litigious society. If my roommates don’t do the dishes, I sue them. Just friendship things.

Testing is a big underlying part of malpractice lawsuits. We talked with Dr. Eric Funk about how this manifests in lawsuits. Do too little testing, you’ll get sued for missing a diagnosis. Do too much testing, you might get sued for complications of over testing. However, the former is much more common, so doctors will test defensively to avoid lawsuits of missed diagnoses.

“A senior partner once told me ‘no one ever sends you a thank you note for not ordering a CT scan’.” - Dr. Eric Funk

What level of risk do we want patients to choose? - If you explain to a patient the risk of over testing AND they choose to pay out-of-pocket, should we let patients assume that risk themselves? I think this argument is at the core of US healthcare - some might find it paternalistic that they’re not allowed to choose themselves, some might find it to be unequal since only the rich can pay, and others might believe that individual patients will always think “it won’t happen to me” and opt for more tests.

The future of screening

Changing evidence-based guidelines for screening - I think one issue is that the screening guidelines aren’t yet personalized enough. Typically it’ll use somewhat blunt characteristics like “age 45-75”. But maybe (probably) our internal biological ages look very different and I have the innards of a 45 year old today. Age, is just like, a societal construct, man. I think as we get more personalized data + cohorting of patients like us, we’ll understand which subpopulations have higher prevalence of disease (e.g. more people named Nikhil have Nikhilitis). That should yield more personalized screening guidelines that will feel like they’re designed for us. It’s also an area I think software can be very helpful, since it’s really about absorbing and interpreting a ton of data points from you, peers, and literature to create a composite screening suggestion.

Blood based biopsies - This conversation seems to mostly come up in tech circles with regard to MRIs, but it’s clear that the new wave of liquid biopsies that scan for signs of cancer is going to be the real tipping point for this discussion. Grail’s Galleri test isn’t FDA approved but has a CLIA waiver, so people or employers can pay for it out-of-pocket. There are many similar tests in the pipeline, too.

Usually cancer tests focus on sensitivity to avoid missing cases since the patients that feel symptoms enough to get tested have a higher likelihood of having the disease. But making these screens part of a regular workup means focusing on specificity instead and trying to avoid false positives. All of this depends on the follow on workups + treatments for a given cancer and the cost/risk of those. But it’s a huge shift in thinking about cancer screening from specific high-risk patients to the general population.

I’m not smart enough to have a strong opinion about whether or not reimbursing these tests and rolling them out widely is the right thing to do. Several articles and studies argue passionately for both sides. But the reality is that it’s already happening - I mean there are now golf tournaments sponsored by liquid biopsy companies.

Patients are going to see ads about a blood test that can find cancer and have a lot of questions about how to get it themselves. Payers are going to get a lot of shit for not covering them. Doctors are going to give them to people and have to have conversations with those that seem to “maybe have cancer” about next steps. This feels like when the dam breaks. And it also feels pretty inevitable in the next couple of years.

Will short term pain create long term solutions? One thing I struggle with is whether massively widespread screening might end up being good in the long run…

Maybe screening the population will create a lot of false positives in the short term, but as a result, we could see increased demand for safer biopsy methods, clinical trials that start at earlier stages in the disease, personalized health baselines for more people that can be used for research down the road, etc.

The Apple Watch is on 100M+ users and now has a single-lead ECG meant to detect heart issues. Understandably, cardiologists are wondering if this is a good thing or going to inundate the health system with people worried about nothing. But what if this results in better systems of triaging patients with at-home testing + telemedicine in order to respond to a massive influx of people wanting answers? What if it better helps us identify rising risk patients with asymptomatic afib who we can manage differently?

Maybe incurring the cost/over testing downsides actually yields more benefits in the form of breakthrough research and better screening in the long run.

Conclusion

I actually think asymptomatic screening is an important conversation with non-obvious answers to reasonable questions. And I hate that whenever this comes up online, it gets so disrespectful and condescending. It really brings out the worst of doctors as gatekeepers and tech people as know-it-alls.

This conversation will also get even more important as diagnostics and screening tools become more specific and widespread.

How do we communicate the downsides of overscreening to the population? I’m not sure they’re going to read a 13-page newsletter…

Thinkboi out,

Nikhil aka. "you weren't an accident, you were an incidentaloma"

Twitter: @nikillinit

Other posts: outofpocket.health/posts

Thanks to Gaurav Singal and Henry Li for reading drafts of this

---

Featured Jobs

Sign up for the featured tier in the Talent Collective to get your jobs in the newsletter, on Twitter, etc.

- Curana Health is a value-based care platform for long term care and senior living. They work with 1,000 senior living community partners across 25 states, servicing over 100,000 patients annually. They're hiring a VP of Data Strategy.

- OXOS Medical is a fast-growing medical technology startup revolutionizing radiology with its handheld, digital x-ray imaging system. They're hiring a marketing leader.

- Sunrise is a metabolic health company that is on a mission to make access to the most effective, cutting-edge treatments available to all. They're hiring a member support lead

{{sub-form}}

---

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, do me a solid and shoot this over to a friend or healthcare slack channel and tell them to sign up. The line between unemployment and founder of a startup is traction and whether your parents believe you have a job.

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 Starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Healthcare 101 starts soon!

See All Courses →Our crash course teaches the basics of US healthcare in a simple to understand and fun way. Understand who the different stakeholders are, how money flows, and trends shaping the industry.Each day we’ll tackle a few different parts of healthcare and walk through how they work with diagrams, case studies, and memes. Lightweight assignments and quizzes afterward will help solidify the material and prompt discussion in the student Slack group.

.png)

Interlude - Our 3 Events + LLMs in healthcare

See All Courses →We have 3 events this fall.

Data Camp sponsorships are already sold out! We have room for a handful of sponsors for our B2B Hackathon & for our OPS Conference both of which already have a full house of attendees.

If you want to connect with a packed, engaged healthcare audience, email sales@outofpocket.health for more details.